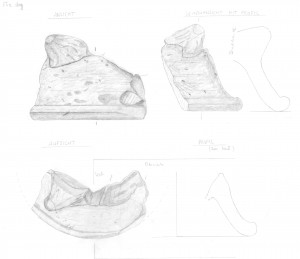

Among the most interesting functional vessel types found in the New Kingdom town of Sai are so-called fire dogs, currently studied by Nicole Mosiniak.

The common assumption is that these vessels were used to hold a cooking pot over a fire. In 2014, thanks to the cooperation and help of the University of Vienna and the NHM, we conducted one experimental project on fire dogs at the “MAMUZ” open-air Museum in Asparn (Lower Austria).

We had several questions we wanted to investigate, first of all the way of manufacture of the fire dogs and their possible function(s). All in all, our experiments showed that cooking is possible with copies of the Ancient Egyptian devices – but it is still not a very convincing way of preparing food, thus Nicole is still taking into consideration also other possible uses respectively a multi-functional use.

This year, an interesting new find came up in SAV1 East. From this sector, until 2014 only five fire dogs were documented – except for one all from surface layers and thus without proper context. This should change during the 2015 season while excavating feature 15.

Feature 15 is a subterranean room located in the central courtyard of Building A. It is of rectangular shape and once had a vaulted roof. Feature 15 is lined with red bricks and red bricks also form the pavement of the structure.

Ashy deposits, large amounts of charcoal, hundreds of dome-palm fruits and abundant animal bones with traces of burning, suggest that feature 15 might have been used as a room for food preparation. Among more than 80 almost intact vessels, mostly plates and dishes, beakers, storage jars and pot stands, there was also a fragment of a fire dog.

SAV1W P163 has a rim diameter of c. 16 cm and shows traces of burning on several spots. It is the first fire dog found on Sai from a sealed context dating to the early-mid 18th Dynasty. Although its function is not explicit, the associated finds from feature 15 might point towards a use within food preparation and here as support for cooking pots. However, it should be noted that only one cooking pot was found in feature 15.

All in all, the fresh finds from feature 15 stress that the large number of fire dogs from Sai might result from a quite complex use of these devices which is still not completely understood.