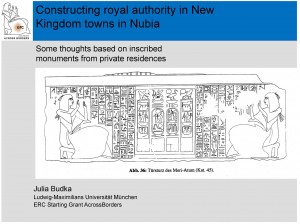

Back in 2016, I presented a paper about aspects of constructing royal authority in Nubian temple towns during the New Kingdom at the 8. Tagung zur ägyptischen Königsideologie in Budapest. The proceedings have just been published and cover a wide and very stimulating range of topics related to royal authority.

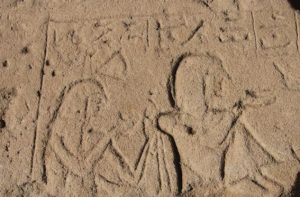

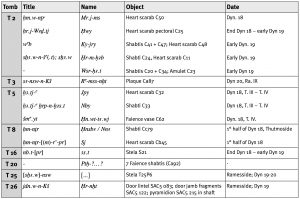

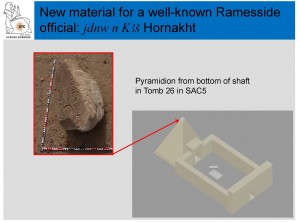

My own contribution focuses on the well-known practice of decorating private residences with scenes of adoring the ruling king, represented by his cartouches, and with corresponding texts giving praise to the king during the New Kingdom. I’ve tried to outline that such scenes and texts are highly relevant for the New Kingdom temple towns of Nubia which were built on behalf of the living ruler within a ‘foreign’ landscape (Budka 2017). Thanks to the recent discoveries by AcrossBorders, a case study from the mid-18th Dynasty (Nehi) and one from the Ramesside period (Hornakht) are used to present the key features of royal authority at the sites and their development during the New Kingdom.

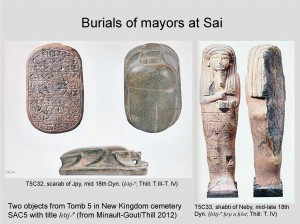

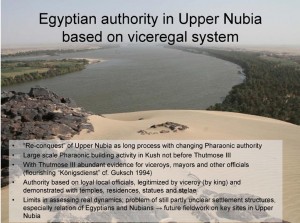

I argue that the cartouche adoring scenes are linked to royal statue cult and deifications of living kings. And here it is necessary to stress that these phenomena were during the mid-18th Dynasty (Thutmose III) primarily restricted to the Nubian region! More precisely to temple towns, which are in many cases, and definitely for Sai, built in areas almost void of earlier Egyptian settlement structures and lacking a strong local priesthood as it was the case back home in Egypt, in the urban centres in Lower and Upper Egypt. The first public display of the adoration of the living king in settlement contexts is in my opinion strongly linked to the character of the sites and the Egyptian administration set up in Nubia with the viceroy of Kush as important representative of the king, fulfilling the role of a mediator.

Interestingly, there is a big change regarding the use of cartouche adoring scenes in Egypt during the time of Akhenaten. These were now becoming standard types in the large villas of his officials in the new town at Amarna. Of course this is connected with the special ideology of kingship under Akhenaten, but certain aspects were until now overlooked: the situation of displaying royal authority and the adoration of deified aspects of the king at Amarna is in some parts quite similar to the temple towns in Nubia. Within a new home away from home and especially far away from long-established priesthoods, the concept of divine kingship was obviously easy to develop further and was then “standardised” – and this can then be traced in Ramesside times both in Egypt and Nubia.

Reference

Budka, Julia. 2017. Constructing royal authority in New Kingdom towns in Nubia: some thoughts based on inscribed monuments from private residences, in: 8. Königsideologie, Constructing Authority. Prestige, Reputation and the Perception of Power in Egyptian Kingship. Budapest, May 12–14, 2016, ed. by Tamás Bács and Horst Beinlich, Wiesbaden, 29–45.