Back in 2013, I was fortunate to participate in the highly interesting 7. Tagung zur Königsideologie (June 26-28 2013), hosted by the Charles University in Prague and dedicated to “Royal versus Divine Authority. Acquisition, Legitimization and Renewal of Power”. The proceedings are now published and I would like to summarise some of my ideas given in this paper (Budka 2015).

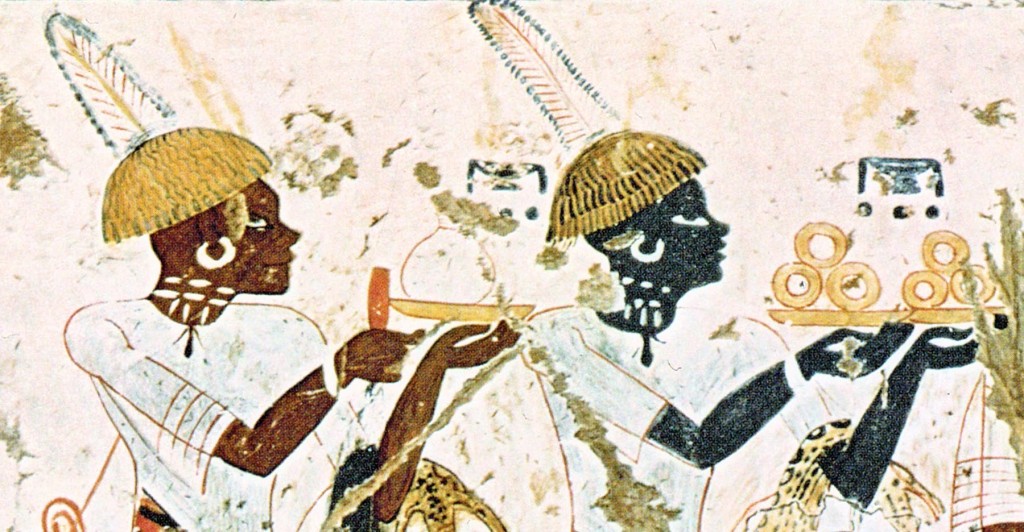

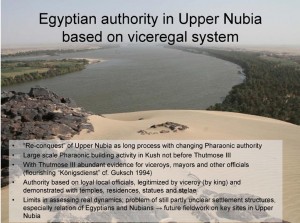

Taking Sai Island and the evolution of its fortified town of the New Kingdom with a small sandstone temple as a case study, I tried to re-examine the evidence for Egyptian authority in Upper Nubia during the Eighteenth Dynasty. Focal points are the viceregal administration, the most important deities, the temples and the royal cult in Nubia. Considerable limits in assessing real dynamics in Upper Nubia during the early New Kingdom are highlighted and the potential of an approach which includes both archaeological and textual sources is stressed.

AcrossBorders’ work on the evolution of the Pharaonic settlement at Sai Island is still in progress – our 2015 field season resulted in many interesting new finds highly relevant for administrative aspects. In 2013, the purpose of my Prague paper was presenting preliminary results and highlighting the potential contribution of settlement archaeology to understand power structures during the New Kingdom.

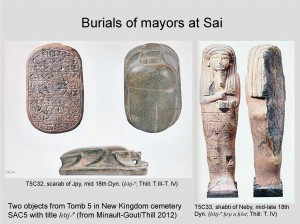

The basic outline of the Egyptian Administration in Nubia is well understood and has been discussed by several scholars, most recently by Müller (2013) and Morkot (2013). Tracing the local administration on a regional level becomes more difficult, and here it is especially challenging to speak about the persons involved. I tried to address in the paper some of the individuals behind the “re-conquest” of Kush and speak about personal dynamics, taking the viceroys of Kush and mayors as examples. Two individuals with the title “H3tj-c” have been buried on Sai (Minault-Gout/Thill 2012), but as yet no in situ evidence for the mayor of Sai was found within the walled town.

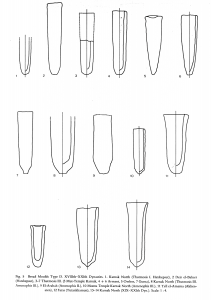

All in all, I hope to have illustrated in the article the changing character of Sai from the reign of Ahmose Nebpehtyra to Thutmose III, very well traceable in both the architecture and the material culture. The “re-conquest” of Kush was a long process with changing Pharaonic authority and differing areas of influence. The new administrative system and the divine kingship established under Thutmose III reflect political changes and altered power structures in Upper Nubia (cf. Török 2009), and within this system Sai developed to become a very important centre.

All in all, I hope to have illustrated in the article the changing character of Sai from the reign of Ahmose Nebpehtyra to Thutmose III, very well traceable in both the architecture and the material culture. The “re-conquest” of Kush was a long process with changing Pharaonic authority and differing areas of influence. The new administrative system and the divine kingship established under Thutmose III reflect political changes and altered power structures in Upper Nubia (cf. Török 2009), and within this system Sai developed to become a very important centre.

Our still limited understanding of the real dynamics in Upper Nubia during the early New Kingdom will hopefully be improved by the ongoing fieldwork on key sites like Sai, Sesebi and others. Quoting from my paper: “At present, it is essential to consider the lack of evidence for Egyptian authority in Kush at the beginning of the New Kingdom, but to carefully distinguish it from confirmed lack of presence.” (Budka 2015, 81).

Our still limited understanding of the real dynamics in Upper Nubia during the early New Kingdom will hopefully be improved by the ongoing fieldwork on key sites like Sai, Sesebi and others. Quoting from my paper: “At present, it is essential to consider the lack of evidence for Egyptian authority in Kush at the beginning of the New Kingdom, but to carefully distinguish it from confirmed lack of presence.” (Budka 2015, 81).

References:

Budka 2015 = J. Budka, The Egyptian “Re-conquest of Nubia” in the New Kingdom – Some Thoughts on the Legitimization of Pharaonic Power in the South, in: Royal versus Divine Authrority. Acquisiation, Legitimization and Renewal of Power, 7th Symposium on Egyptian Royal Ideology, Prague, June 26-28, 2013, ed. by F. Coppens, J. Janák & H. Vymazalová, Königtum, Staat und Gesellschaft früher Hochkulturen 4,4, Wiesbaden 2015, 63-82.

Minault-Gout/Thill 2012 = A. Minault-Gout, F. Thill, Saï II. Le cimetière des tombes hypogées du Nouvel Empire (SAC5), Fouilles de l’Institut Français d’Archéologie Orientale 69, Cairo 2012.

Morkot 2013 = R. Morkot, From conquered to conqueror: the organization of Nubia in the New Kingdom and the Kushite administration of Egypt, in J. C. Moreno García (ed.), The Administration of Egypt, Handbuch der Orientalistik 104, Leiden 2013, 911-963.

Müller 2013 = I. Müller, Die Verwaltung Nubiens im Neuen Reich, Meroitica 18, Wiesbaden 2013.

Török 2009 = L. Török, Between Two Worlds: The Frontier Region between Ancient Nubia and Egypt 3700 BC – 500 AD, Probleme der Ägyptologie 29, Leiden 2009.