One of the main tasks of the AcrossBorders project was investigating the New Kingdom population and answering questions about not only the individual lifestyles, but also the origin of the persons. Were the people who lived in the New Kingdom Egyptian town on Sai and were buried in the pyramid cemetery SAC5 Egyptians, or Nubians – or rather a mix of both and the evidence of ‘cultural’ respectively ‘biological’ entanglement?

I am very proud to announce that our paper on the application of strontium isotopes to investigate cultural entanglement in Sai and its surroundings is now out and published (Retzmann et al. 2019)! The main author is Anika Retzmann and many thanks go of course to her and the complete team of authors!

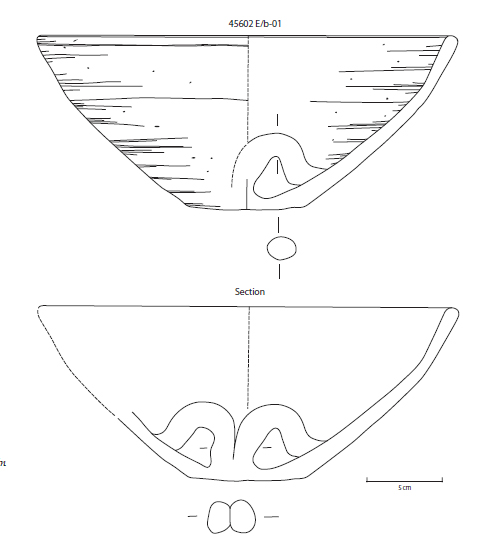

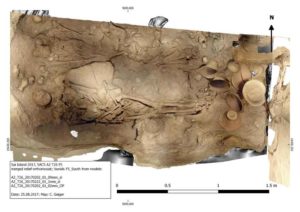

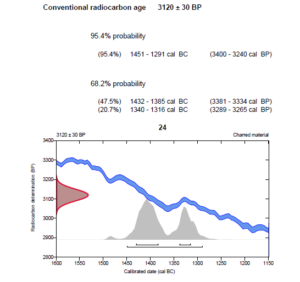

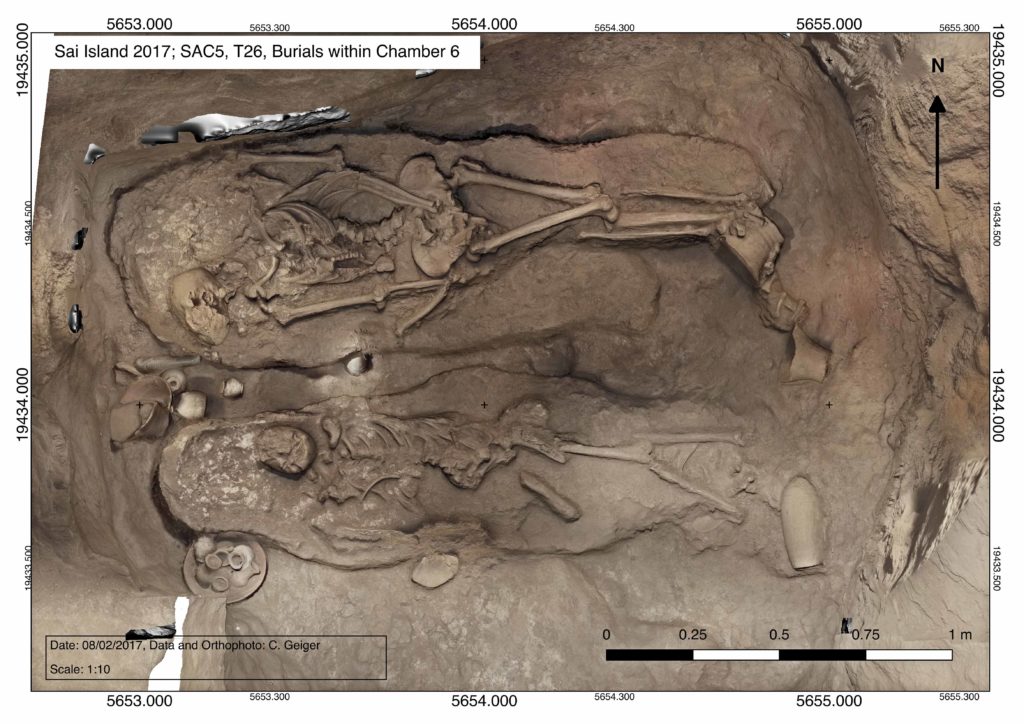

Strontium isotopes were applied to identify possible ‘colonialists’ coming from Egypt within the skeletal remains retrieved from Tomb 26 of the pharaonic cemetery SAC5 on Sai Island. Tooth enamel of nine individuals including the Overseer of Goldsmiths Khummose and his presumably ‘wife’, dating from the 18th Dynasty, were investigated to gain information whether these individuals were first generation immigrants from Egypt or indigenous members of the local population inhabiting the area of Sai Island.

The local strontium signal on Sai Island during the New Kingdom was derived from archaeological animal samples (rodent, sheep/goat, dog and local mollusc shells, all dating from the New Kingdom) in agreement with local environmental samples (paleo sediments and literature Sr isotope value of Nile River water during the New Kingdom era).

As you can read in more detail in the article: the strontium values suggest that all people buried in Tomb 26 are members of the local population. A striking outcome, since the tomb, the tomb equipment, the personal names and titles are all clearly ‘Egyptian’.

To make it short: our results are simply exciting, tie in nicely with similar research at Tombos and Amara West – and will be of great importance also for my new DiverseNile project. More information on the complex coexistence and biological and cultural entanglement of Egyptians and Nubians during the New Kingdom are urgently needed. In this respect, we will continue to investigate the isoscape in my new concession – I am very happy that the successful team who did this for Sai will be again involved! The MUAFS area will provide new data from soil, water, molluscs and of course animal bones and human teeth which will allow us to place the data from Sai in a broader context. The periphery of Sai and Amara West, our Attab to Ferka region, also has rich potential to check the validity of our present strontium analysis.

Reference

Retzmann et al. 2019 = Anika Retzmann, Julia Budka, Helmut Sattmann, Johanna Irrgeher, Thomas Prohaska, The New Kingdom population on Sai Island: Application of Sr isotopes to investigate cultural entanglement in ancient Nubia, Ägypten und Levante 29, 2019, 355–380