With a splendid evening lecture by Dominique Valbelle, the AcrossBorders workshop “Settlements patterns in Egypt and Nubia” came to an end. I am very grateful to all participants for making it a successful and also very pleasant event! Special thanks go to all AcrossBorders’ team members and the LMU students helping with the organization. The location of the workshop was just perfect – many thanks again to the Egyptian State Museum Munich – and here not only to the first and second directors Silvia Schoske and Arnulf Schlüter, but also to Dietrich Wildung. His special offer of a guided tour through the galleries was much appreciated by all participants – it complemented the programme of the workshop in a perfect way and illustrated the complex and changing relations between Egypt and Nubia/Sudan throughout the millennia.

Most talks were concentrating on settlement architecture and the planning of settlements. Ingrid Adenstedt presented her 3D reconstruction of the Pharaonic town on Sai – from my perspective a very big step forward for a better understanding of the evolution of the site! Florence Doyen shared her by now much advanced assessment of SAV1 North, proposing interesting ideas about the layout and foundation of the town on Sai.

Cornelius von Pilgrim impressed everyone with speaking about the intriguing house 55 on Elephantine island – I really can’t wait for our upcoming field season to go back there and continue sorting out the complex phases of use of this unusual structure!

Amara West and its huge potential were beautifully presented by Neal Spencer – the state of preservation of the mud brick houses is simply amazing. Manfred Bietak closed Day 1 with new observations on the structure and function of the monumental palace of the Middle Kingdom in Bubastis.

Day 2 was opened with a very interesting session dedicated to settlement patterns in Prehistoric times and to the Pre-Kerma and Kerma periods. Elena Garcea presented her work at Khartoum Variant, Abkan and Pre-Kerma sites at Amara West and on Sai – and was able to pose some thought-provoking questions highly relevant also for the historic periods.

Giulia D’Ercole and Johannes Sterba presented their ongoing chemical analyses of Nubian and Egyptian style sherds from Sai. Johannes got huge complements afterwards: “A contribution by a scientist which was completely understandable!” Of course I totally agree.

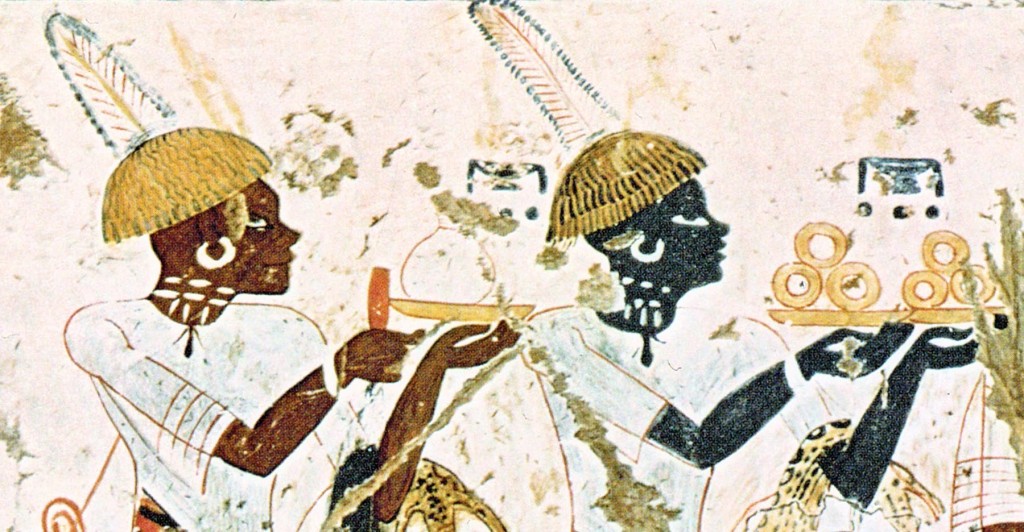

Recent discoveries in the ceremonial city of Kerma were the topic of Charles Bonnet’s talk – he showed beautiful 3D reconstructions of these very peculiar buildings of an African kind of architecture. Kate Spence used Sesebi as a case study to pose several key questions for our understanding of so-called temple towns. Her assessment that it is crucial to understand the foundation processes of these sites seems especially noteworthy.

Stuart Tyson Smith led us to Tombos, one of the major bounderies between the Nubian and Egyptian realm during the New Kingdom. He focused on a very large, enigmatic building of 18th Dynasty date found in recent excavations. So much more remains to be excavated at this important site at the Third Cataract!

The last afternoon session was dedicated to 18th Dynasty Egypt – the important site of South Abydos, the Ahmose town, was presented by Stephen Harvey. He addressed not only the oracle cult of Ahmose, but also interesting ideas about ancestor’s cult.

The paper by Anna Stevens was the perfect transition to the final discussion: Anna addressed community and sub-communities at Amarna and raised important issues. “How much did the occupants feel they are part of their/a community” would nicely apply to open but crucial questions we have regarding the occupants of Egyptian sites in Kush – all of us working there have found increasing evidence for a complex social stratification and the entanglement of Egyptian and Nubian cultures.

Dominique Valbelle considered a wide range of textual records for the assessment of settlement patterns in Egypt and Nubia – most importantly, she showed us new material from the excavations in Dokki Gel.

Without doubt, the ongoing excavations of the international missions working in Northern Sudan have widened our understanding of the complexity of settlement patterns in Nubia. There is some hope that we will continue in these lines and might also be able to learn more about Egyptian urbanism by taking into accounts the sites located in Kush.