Among other things we have been busy with reconstructing the history of research of Sai Island in the last weeks. Jördis collected all bibliographical data and available illustrations, especially of descriptions of the Ottoman fortress and the state of its ruins – in doing so we are hoping to get a better understanding of the multifaceted formation processes of the site, especially the state of preservation of the Pharaonic town which was overbuilt by the later fortress. It is therefore essential to review which blocks, columns and other worked stones were observed at what time and whether this corresponds to the current position of the stones blocks.

Current state of the ruins at Sai: remains of the New Kingdom town within the Ottoman fortress (view towards the Southeast).

Spending this week in Berlin, I am not only meeting current and hopefully future team members, but I am also using the libraries here to check some of the travellers’ accounts we have been unable to trace in Vienna. Among the early travellers and explorers who visited Sai Island were Cailliaud, Hoskins, Bonomi, Wilkinson, Lepsius, W.A. Budge and also Louis M. A. Linant de Bellefonds. The latter was exploring the island on June 5, 1822 and I found his published report yesterday at Humboldt University. He describes the beauty of its landscape and also its archaeology – being full of monuments from the Egyptian, Christian and Ottoman eras. His focus is – like of the other early travellers – on the dominant monument, the Ottoman fortress, of which he left us a beautiful view in water colours. But Linant de Bellefonds also mentions Pharaonic blocks within this castle. He describes in particular the Ottoman gate of the fortress in the south – and notes that it was built with several reused blocks, some of them coming from a Pharaonic temple.

Reused blocks forming the southern gate of the Ottoman fortress (Jan. 2014, photo: Nicole Mosiniak).

What stroke me in particular while reading his description yesterday is the following sentence: « Il y a parmi ces pierres [clearly referring to stones around the gate] les restes de deux statues qui paraissent avoir été d’un bien beau travail. » (Shinnie 1958: 191). Two statues of good quality – maybe I am here just a typical victim of Egyptological subjectiveness, but I was immediately thinking of the two seated royal statues of Ahmose Nebpehtyra and Amenhotep I. Could they have been visible already in the 1820ties? It was Blackman and Fairman who reported the discovery of the lower part of the Ahmose’s statue in 1937 – having been found in the Ottoman fortress (see Arkell 1950: 34).

The two statues are now in the Khartoum National Museum and are among the most debated monuments from Sai (Davies 2004; Gabolde 2011-2012) – there is an ongoing argument whether the statue of Ahmose was set up during his lifetime (e.g. favored by Vivian Davies) or was a post-mortem monument erected by his son Amenhotep I (as e.g. believed by Luc Gabolde). It also remains unclear where the statues were originally standing – the small Amun-Ra temple (Temple A) located north of the Ottoman citadel dates to a later time (Thutmose III). I have proposed last year at conferences in Prague and London that these heb-sed statues are likely to belong to so-called Ka-chapels of the kings. Such chapels are known to have been located outside of fortresses during the Middle Kingdom and are sometimes simple mud brick structures – maybe explaining why a hwt-ka has not yet been found on Sai.

Upper part of the Ahmose Nebpehtyra statue from Sai, now in the Khartoum National Museum – its head was found a bit further south than the lower part (Davies 2004).

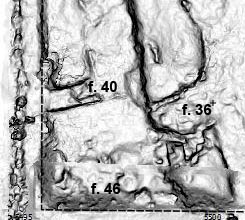

Even if the statues seen by Linant de Bellefonds are not the ones of Ahmose and his son, I understand his account as an important hint that most of the Pharaonic statues discovered within the town area of Sai actually come from a well-defined and specific area: the southern part of the Ottoman citadel, especially from the surroundings of its gate. Whether this indicates a still unknown building near-by or simply reflects the gathering of dismantled Pharaonic structures at the steep slope towards the south remains uncertain for now. We will try to pay special attention to this part of Sai in the upcoming years hoping to be able to understand more of the very complex history of the site.

References:

Arkell 1950 = A. J. Arkell, Varia Sudanica, JEA 36, 24–40.

Davies 2004 = W. V. Davies, Cat. 76, Statue of Amenhotep I, 102–103, in: D. A. Welsby and J. R. Anderson (eds.), Sudan. Ancient Treasures. An Exhibition of recent discoveries from the Sudan National Museum, London.

Gabolde 2011-2012 = L. Gabolde, Réexamen des jalons de la présence de la XVIIIe dynastie naissante à Saï, CRIPEL 29, 115–137.

Shinnie 1958 = M. Shinnie (ed.), Linant de Bellefonds: Journal d’un voyage à Méroé dans les années 1821 et 1822, Occasional papers, Sudan Antiquities Service 4, Khartoum.