Since the beginning of my studies, I always regarded king Ahmose Nebpehtyre as one of the key figures of Egyptian history. Having studied in Vienna with Manfred Bietak, the excavator of Avaris, the ancient Hyksos capital which was taken by Ahmose as the first king of the 18th Dynasty, this is of course no surprise. I was furthermore fortunate to join Stephen Harvey and his excavation in the Ahmose complex at Abydos in 2002 – ceramics datable to the reign of this king were now in my hands and have occupied me since then!

Joining the SIAM at Sai and especially with establishing AcrossBorders, Ahmose Nebpehtyre is now definitely one of the focal points of the project.

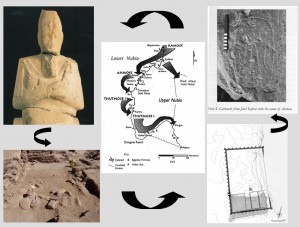

I am therefore delighted that an important epigraphic evidence of the king from Upper Nubia was just published in the new issue of Sudan & Nubia: Vivian Davies presents the fascinating results of the expedition led by Frederik William Green (1869-1949) from Halfa to Kareima in the winter of 1909-1910. Among the meticulous epigraphic documentation by Green there is not only the well-known building inscription by viceroy Nehi from Sai (Davies 2014, 7-8), but also the cartouche of king Ahmose Nebpehtyre near Jebel Kajbar, at Jebel Noh (Davies 2014, 9-10). It was rediscovered by the survey of the University of Khartoum and first published by Edwards with a photograph (Edwards 2006, 58-59, pl. 4). Davies can now provide the complete set of data: Green’s original copy of the cartouche, a photo and a new copy. He stresses the historical importance of this rock engraving: “It provides direct in-situ evidence of an Egyptian presence far south at the Third Cataract during the reign of the first king of the 18th Dynasty.” (Davies 2014, 10). He rightly adds to this: “Since the inscription is currently an isolated case, caution is required in drawing any firm conclusions at this point as to the nature of this presence.” (Davies 2014, 10). I strongly agree with Vivian Davies about the historical significance of this cartouche and that the precise nature of the earliest Egyptian occupation in Upper Nubia still has to be established by future excavations and a consideration of all sets of data (ceramics, archaeological evidence and textual sources).

The complete set of data will allow a re-assessment of the presence of the early 18th Dynasty in Upper Nubia.

For Sai, we can definitely attest an Egyptian presence in the earliest New Kingdom. The earliest strata within the Pharaonic town date, according to the ceramics, to the period of Ahmose Nebpehtyre to Thutmose I. This nicely complements the textual sources from the island, which also include references to Ahmose, especially his famous sandstone statue (Gabolde 2011–2012, 118-120).

Several Nubian campaigns are attested by king Ahmose Nebpehtyre (Morris 2005, 70-71), but we still know little about the precise setting of his battles and activities against the kingdom of Kerma. This is why the Jebel Noh cartouche is of such importance.

All in all, the ongoing archaeological work on Sai Island, and new evidence such as a rock engraving of king Ahmose Nebpehtyre close to the Third Cataract, support the idea that Sai functioned during the early 18th Dynasty as a “bridgehead into Kush proper and a secure launching pad for further campaigns” (Davies 2005, 51). With excavations at other sites like Sesebi and Doukki Gel we are currently getting closer to understand the Egyptian activities in Kush during the early New Kingdom.

References

Davies 2005 = Davies, W. V., Egypt and Nubia. Conflict with the Kingdom of Kush, in C. H. Roehrig (ed), Hatshepsut: From Queen to Pharao, New York, 2005, 49-56.

Davies 2014 = Davies, W. V. 2014. From Halfa to Kareima: F. W. Green in Sudan, Sudan & Nubia 18, 2014, 2‒19.

Edwards 2006 = Edwards, D. N., Drawings on rocks, the most enduring monuments of Middle Nubia, Sudan & Nubia 10, 2006, 55-63.

Gabolde 2011–2012 = Gabolde, L., Réexamen des jalons de la présence de la XVIIIe dynastie naissante à Saï, CRIPEL 29, 2011-2012, 115–137.

Morris 2005 = Morris, E. F., The architecture of imperialism. Military bases and the evolution of foreign policy in Egypt’s New Kingdom, Probleme der Ägyptologie 22, Leiden/Boston 2005.