After taking part in two campaigns on Sai Island (see: The Architectural Survey Part 1 and Part 2 and the 3D-Laserscanning Campaign), I am now happy to announce that I have joined the team of AcrossBorders in the beginning of October, which enables me to fully focus on the architectural research of the New Kingdom town on Sai Island.

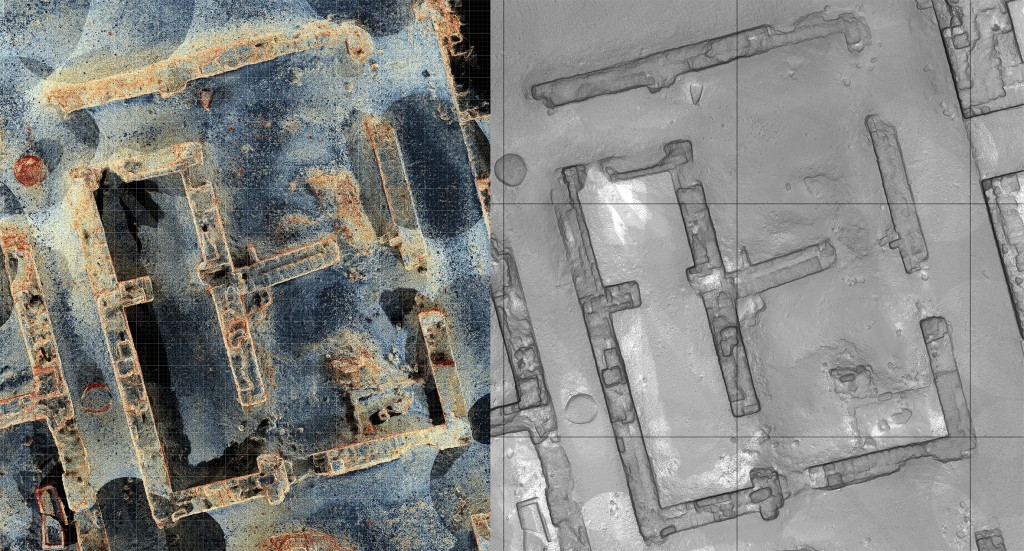

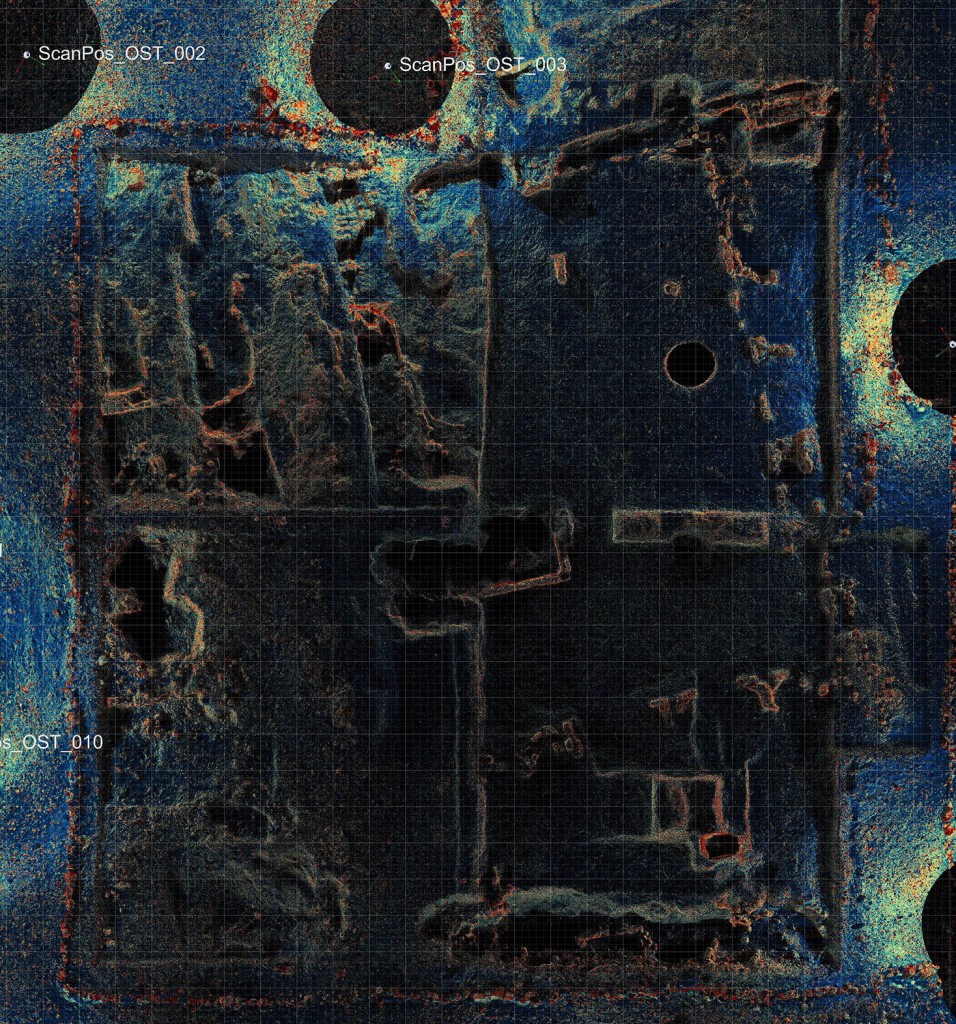

In the past months, my colleague from the Technical University of Vienna Robert Kalasek figured out a workflow for the post-processing of the huge amount of scan-data that we had acquired during our stay on Sai Island in February. This post-processing includes steps such as registering the single scans together and then cleaning the resulting 3D point cloud, i.e. removing any unwanted information and noises. After carrying out these steps and taking certain vital settings, such as the deviation, the range and the reflectance into consideration, a smooth data transfer into a further post-processing software was possible. In our case we are using the software PointCab, which enables us to create plans and sections directly from the 3D point cloud, which can be further worked out in AutoCAD.

After Robert had already prepared some of the ground plans, my first task was to completely revise the ground plan that I had generated last year. The “old” plan was solely based on the sketches and measurements that I had carried out in my first year on Sai and therefore was lacking in accuracy in some parts. With the new laser scanning data, it was now possible to create an exact and – most importantly – a geo-referenced ground plan of the southern area of the Pharaonic town. At this point I would like to stress however, that my hand measurements and sketches were not in vain, since I believe that to really get to know a building and the structure you have to look really closely and carry out old-fashioned hand measurements to “get a feel” for it. Together with the 3D-data, these basics of documentation serve as the perfect combination for drawing analytical plans.

In a further step it is planned to integrate the newly excavated areas (SAV1 East and SAV1 West) as well as SAV1 North into this new plan. On the one hand, these areas were also scanned and geo-referenced, on the other hand they were exactly documented in the course of the excavation. Both of these results can easily be incorporated into the final map of the area. Also, work on detailed plans on the respective buildings in the form of accurate stone-by-stone (or rather brick-by-brick) plans has commenced and will be continued over the next few weeks.

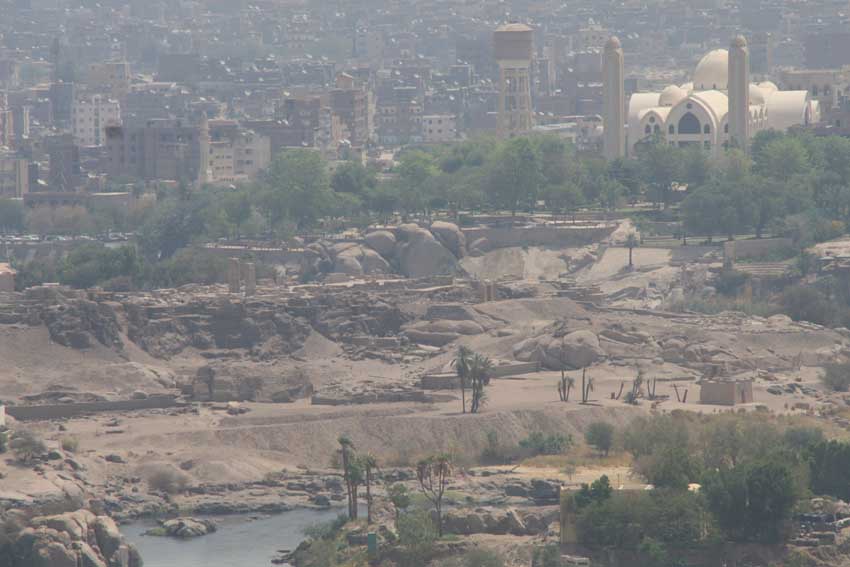

Since a major part of my future work will focus on a reconstruction/visualization of the New Kingdom town, which shall have a strong scientific basis, I have started to look for comparative architecture in other settlements, e.g. Amarna and Elephantine in Egypt or Amara-West, Askut and Sesebi in Sudan. Different aspects of settlement architecture have to be taken in account, such as residential and administrative buildings, storage facilities, the fortifications and the entrance gate. The specific layout of the towns is being investigated as well, so that possible new conclusions for Sai can be made, especially taking into account that of now we still know little of the northern part of the town.

Going into more detail, other aspects I wish to elaborate on are the specific building types and also the building techniques used at the different houses.

In conclusion I can say that I am very much looking forward to the upcoming months and working with the architectural remains of Sai Island, which is certainly a very exciting field of work!