Since I joined AcrossBorders, my main focus of research has been the object studies from settlement sites in Egypt and Sudan. During the first months I have been reading through excavation reports from different settlement sites e.g. Amarna, Elephantine, Memphis, Qantir, Tell el-Retaba in Egypt and Amara-West, Askut, Sesebi and of course Sai in Sudan. The focus of interest was especially laid on New Kingdom objects such as tools and instruments (e.g. hammers, pounders, mortars, grinding stones, scrapers, weights and cosmetic palettes), personal adornments (e.g. pearls and amulets), household items (e.g. mud stoppers, sealings and furniture), figurines and statuettes, stone and faience vessels and different kind of other small objects such as models, games and scarabs. Whilst I have been reading the excavation reports I have simultaneously been building a structured literature database (using also Citavi like for our general reference database) organized according to different settlement sites and object categories. This preparation should help me in categorizing and contextualizing the objects to be found in upcoming excavation seasons at Elephantine.

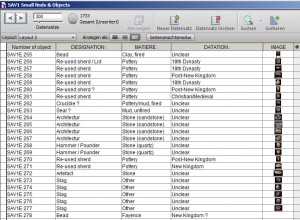

Meanwhile I have been also looking at the small finds & objects database from previous excavations (2008-2014) at Sai and comparing that material with those found at the other settlement sites in Egypt and Sudan (see Budka & Doyen 2012-2013, 182-188 for more details). As I come from Finland where fishing is a common hobby, a few objects caught my special attention – more about the connection of these objects and fishing further below. The discussion of these objects here does not present a final and complete conclusion but should be seen more as an input for a debate.

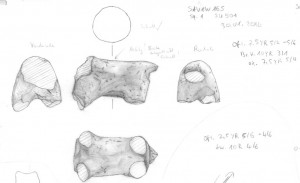

Object SAV1N/0601 (© SIAM)

The two here presented objects are described as follows. The first object SAV1N/0601 is a fragment of a rectangular piece of sandstone (7.4 x 8.4 x 3.1 cm) with rounded corners on one end. The peculiarity of this object are the two carved parallel grooves – one deeper than the other and running through the whole object surface getting slightly narrower the closer it gets to the broken edge. The second object SAV1N/2031 is also a sandstone fragment (8.2 x 7.3 x 4.1 cm) with a smooth surface. Along the surface of this object there are also two grooves. They are not running parallel but crossing each other oblong. These objects do not make out an exception in the material as there are other sandstone objects with similar characteristics e.g. SAV1N/0415, SAV1N/1432, SAV1N/1728, SAV1N/2174, SAV1N/1767 and SAV1N/2387.

Object SAV1N/2031 (© SIAM)

While some of the objects cannot be dated because they come from unstratified/mixed contexts in SAV1 North, others are well attributable to the 18th Dynasty. SAV1N/2031 was found in a late phase of (re-)use of house N12, SAV1N/2174 can be associated with its prime use, dating to Thutmoside times (see Budka & Doyen 2012-2013, 176-177 and 182). Functional aspects of these objects, presumably of New Kingdom date, are not straightforward. I came across a broad variety of possible interpretations.

The first parallel comes from Tell el-Retaba, a major Dynastic-period site in Northern Egypt. In the excavation report about the New Kingdom remains (18th and 19th Dynasties) appears one sandstone object labelled as “whetstone” (Rzepka et. al. 2012-2013, 267-268, Figures 34 and 35). This flat rectangular piece of sandstone (7.3. x 7.4. x 3.4 cm) is complete in preservation, with numerous narrow grooves on the surface. According to the excavators these grooves are the result of the stone being used as a tool sharpener (Rzepka et. al. 2012-2013, 268, footnote 41 with further parallels). Though which tools were sharpened, is not discussed.

Another parallel comes from the Ramesside workshops at Qantir. In her impressive monograph about the stone- and metalworking tools and instruments Silvia Prell presents a variety of stone objects for grinding, rubbing and polishing the end-products (“Werkstück”) and whetting and sharpening of metal tools as also arrowheads e.g. made of bone (Prell 2011, 44-72). One of the characteristics of the “Schleifsteine” is that they mainly consist of quartzite. They were in general used as tools to work on the surfaces of the end-products. In contrast, the objects (“Wetzsteine” = whetstone) to sharpen metal tools consist mainly of sandstone (Prell 2011, 48). Some of the whetstones from Qantir possess grooves as found at Tell el-Retaba and Sai (Prell 2011, 48 and 52-53). As an example the complete conserved trapezoid whetstone Kat-Nr. 166 (5.5 x 5.1 x 2.2 cm) possess one clearly recognizable groove (Prell 2011, 51, Plate 05 and Catalogue p. 180). Left to this groove there is probably the mark of a second one. Silvia Prell states that the choice of sandstone for whetting and sharpening of metal tools such as knives and adze is not accidental; sandstone is well suitable for this purpose (Prell 2011, 48, 50 and 52). However, no remains of bronze or copper rust were found inside the grooves at Qantir. According to Prell the grooves seem not to be carved intentionally but originate from the constant whetting of metal tools on one place (Prell 2011, 52).

The last parallel presented here comes from recent excavations at Amarna. A group of sandstone objects are labelled as sanders to smoothen wooden surfaces (Kemp & Stevens 2010, 437-441). One sandstone object 37185 (9.4 x 6.7 x 2.3 cm) with a smooth but irregular surface has two shallow grooves (Kemp & Stevens 2010, 437, Figure 22.10 and Plate 22.7). The excavators interpret these grooves as result of extracting sand grains from the object; sandstone was imported to Amarna as it was not locally accessible (Kemp & Stevens 2010, 437-438). A similar interpretation is given to explain the narrow grooves on a travertine grinding-block (Kemp & Stevens 2010, 422, Figure 22.5 and Plate 22.5).

So coming back to the objects from Sai: Could they be whetstones for sharpening metal tools, stone pieces to extract sand grains or may the marks even be left overs of cutting stone? Above, I started this excursus mentioning a possible connection of these objects to fishing; what do I mean with that? As a child I was sometimes fishing with people who really knew what they were doing, so to say experts in their hobby. At that time I learned how to sharpen fishing hooks. Of course you can do this with just a flat whetstone. However, much easier is to take a special whetstone with a prior made groove and to grind the hook in that groove back and forth changing the angle at times. This is the reason why my interest was especially caught on these objects.

This analogy and hypothesis is of course a bit adventurous. The objects themselves do not give any clear evidence for their usage. As mentioned above they come from various contexts at settlement sites, mostly houses and workshops. Is the occurrence of these objects a phenomenon of a horizontal usage or are they scattered finds across time? As presented above, such objects are attested in New Kingdom settlement contexts in Egypt. The analysis of the function of these objects remains a tricky one. If we take into account that as yet, no fishing hooks have been found in New Kingdom contexts at Sai, the ground for the interpretation of these objects in connection with fishing hooks is clearly thin (bronze and copper alloy hooks for fishing are well attested from New Kingdom settlement contexts, see e.g. hooks in the MMA from Lisht North, accession number 09.180.748, 09.180.750 and 09.180.764 for smaller ones 1.9-4.1 cm and 22.1.954 for a bigger one 8.1 cm, though from the cemetery). It is worth mentioning that the Pharaonic town of Sai has yielded evidence for fishing by large numbers of net weights.

Whetstones for sharpening fishing hooks require intentionally made grooves, therefore the grooves should be examined in more detail. Different kinds of grooves for different kinds of tools? The fishing hook hypothesis would of course exclude the possibility that the grooves were the result of sharpening, e.g. knives and adzes. I am not an expert in sharpening blades, but I think it is much more effective to hold a blade parallel to a stone and moving it along the surface than in an angle where it cuts the stone. In that case, sharpening should not result in any grooves (Prell 2011, 48-52; Kemp & Stevenson 2010, 443-444 for whetstones without grooves). If the stones were used as row material for the production of sand grains (as proposed for pieces from Amarna), it raises the question for what purpose?

So this excursus about “groovy” stone objects has actually put more questions into light than answers. Anyhow, if documented and examined accurately, they are a valuable source of information about life in settlements in ancient times.

References

Budka, J. & Doyen, F.

2012-2013 Living in New Kingdom towns in Upper Nubia – New evidence from recent excavations on Sai Island, Ägypten und Levante XXII/XXIII, 167–208.

Kemp, B. J. & Stevens, A. K.

2010 Busy lives at Amarna. Excavations in the main city (Grid 12 and the house of Ranefer, N49.18), Vol. II: The objects, Excavation memoir 91, London.

Prell, S.

2011 Einblicke in die Werkstätten der Residenz. Die Stein- und Metallwerkzeuge des Grabungsplatzes Q I, Die Grabungen des Pelizaeus-Museums Hildesheim in Qantir-Piramesse, Forschungen in der Ramses-Stadt 8, Hildesheim.

Rzepka, S., Nour el-Din, M. et al.

2012-2013 Egyptian mission rescue excavations in Tell el-Retaba. Part 1: New Kingdom remains, Ägypten und Levante XXII/XXIII, 253–288.