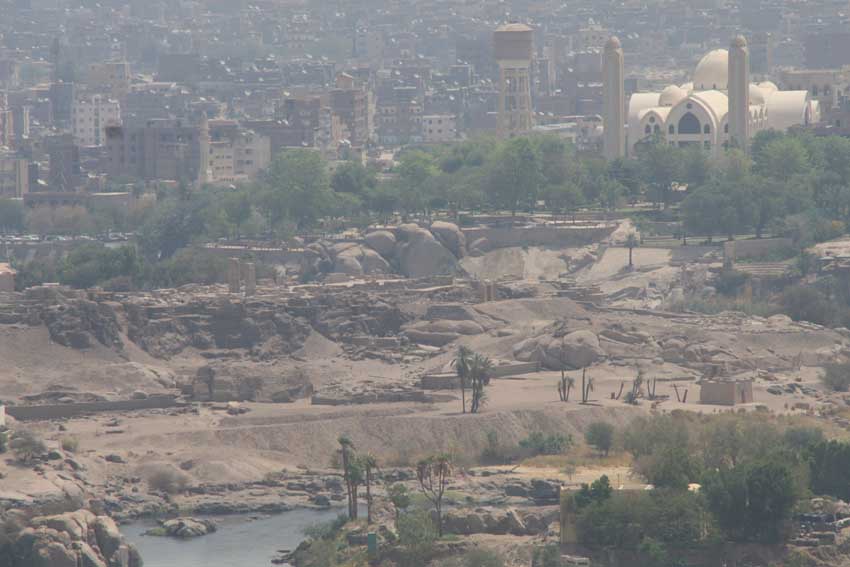

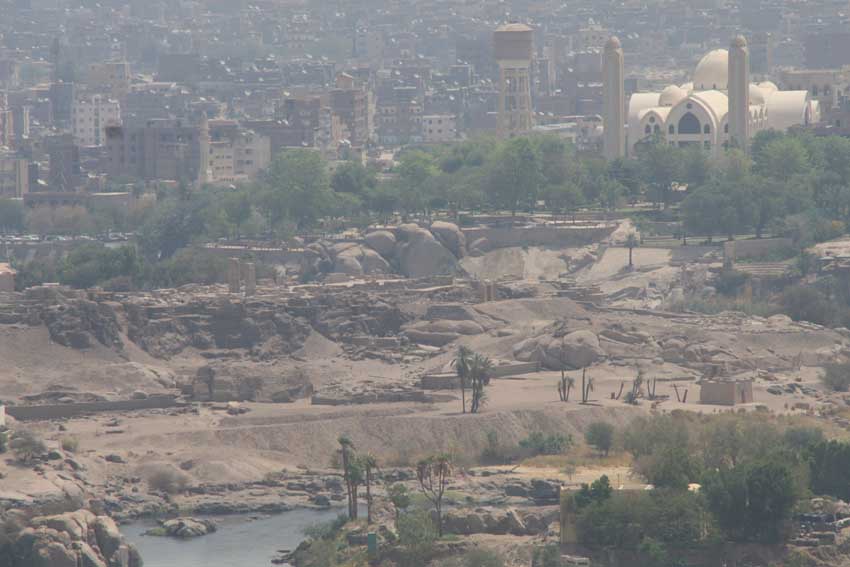

Remains of the ancient town in the southern part of Elephantine Island.

The importance of Elephantine as site with strategic value due to its location just north of the First Nile Cataract is well known. More than forty years of excavations by the joint German-Swiss mission have considerably increased our understanding of this beautiful island in Egypt’s South.

For a long period Elephantine functioned as base for Pharaonic expeditions to Nubia and as important trading point at Egypt’s southern border (cf., e.g., von Pilgrim 2010). With the so-called reconquest of Nubia, the Egyptian expansion towards the South during the 18th Dynasty, there was an increased demand for the transport of goods, materials and people to and from Upper and Lower Nubia. Elephantine flourished and gained significance during the early New Kingdom and especially in Thutmoside times.

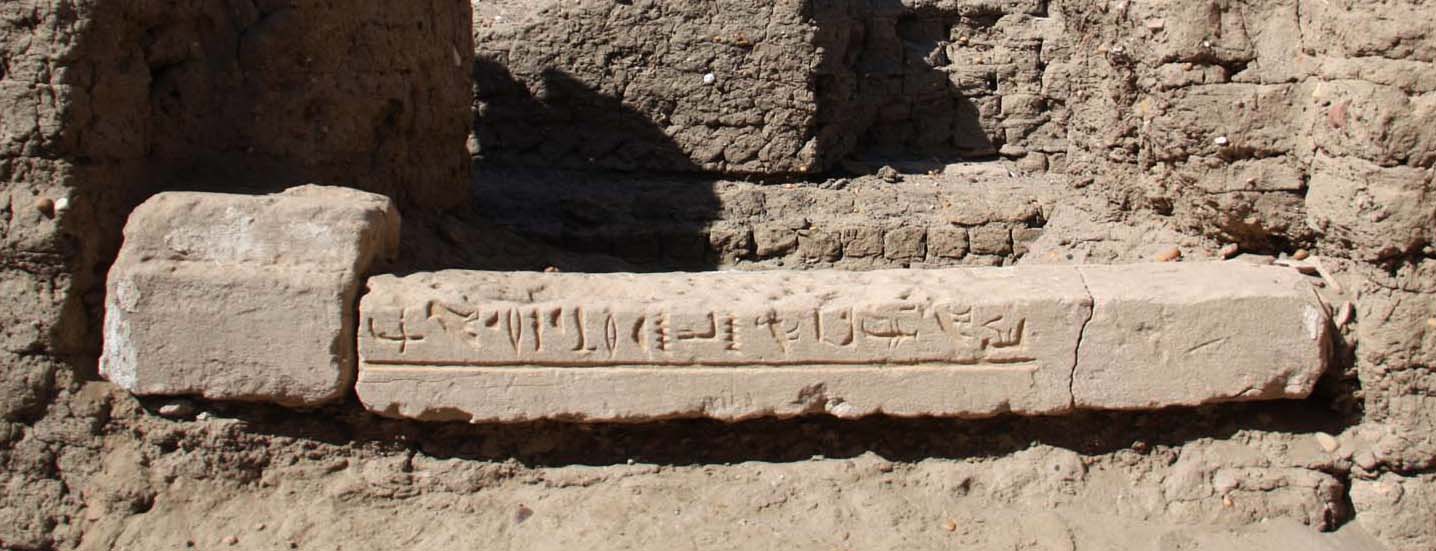

Egyptian officials who participated in expedition and/or military campaigns towards the South had to pass through the First Cataract region. Obviously they spent some time there, at Aswan and Elephantine, before their departure to Nubia as hundreds of rock inscriptions attest (cf. Gasse/Rondot 2007; Seidlmayer 2003).

Further first hand testimony for the presence of these officials comes directly from the settlement of Elephantine – inscribed door jambs attest well-known individuals like viceroy Nehi. Of special interest is the context of these epigraphic sources: living conditions of people like Nehi traceable by the architecture and material culture. For the latter, ceramics are of high significance allowing reconstructing aspects of the daily life like food production and consumption and much more.

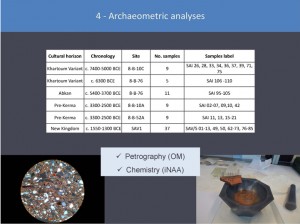

Within the framework of AcrossBorders, it is therefore of key importance that the 18th Dynasty pottery from Elephantine provides very close parallels to the corpus excavated at Sai (cf. Budka 2011). Within the next years, a detailed comparison of the two sites is planned and the ceramics form main elements of this study. This week, we just started our 2014 season of documenting and processing pottery at Elephantine thanks to our cooperation with the Swiss Institute Cairo and kindly supported by the German Archaeological Institute.

The focus is on material from the very early to the mid-18th Dynasty: Bauschicht/level 10 at Elephantine corresponds to levels 5-4 and the early phase of level 3 at Sai Island. Thanks to the stratigraphy at Elephantine, where several phases within one building from a certain building level are much better preserved than at Sai, a fine dating of the material from the earliest occupation at both sites seems possible in the near future.

Having just started to work with the material, the close comparisons are striking me once again: the main types of vessels are consistent at both sites and include carinated bowls and dishes, plates, footed bowls, stands, beakers and beer jars, cooking pots, storage jars, water jars as well as decorated jars and Nubian vessels.

Differences can be noted in small details – for example regarding the quantities of certain wares and fabrics or technical features of the finished vessels. All in all, we have now a considerable amount of data and material and these are supporting my first assessment published in 2011: The comparison between the material from Sai and Elephantine and especially the imported Nile clay and Marl clay vessels at Sai suggest for at least part of the corpus a provenience from the First Cataract area illustrating the importance of Elephantine as trading point and for equipping expeditions and settlements located in the South (Budka 2011, 29) .

References

Budka 2011 = Julia Budka, The early New Kingdom at Sai Island: Preliminary results based on the pottery analysis (4th Season 2010), Sudan & Nubia 15, 23–33.

Gasse/Rondot 2007 = Annie Gasse and Vincent Rondot, Les inscriptions de Séhel, Cairo 2007.

von Pilgrim 2010 = Cornelius von Pilgrim, Elephantine – (Festungs-)Stadt am Ersten Katarakt, in Cities and Urbanism in Ancient Egypt, eds. Manfred Bietak, Ernst Cerny and Irene Forstner-Müller, Vienna 2010, 257–265.

Seidlmayer 2003 = Stephan J. Seidlmayer, New Rock Inscriptions on Elephantine Island, in Egyptology at the Dawn of the Twenty-first Century, Proceedings of the Eighth International Congress of Egyptologists Cairo 2000, ed. Zahi Hawass, Vol. 1, Cairo 2003, 441–442.

“Sâî is a difficult place to reach, unless the traveller has his own boat with him. On January 2nd, 1821, Cailliaud crossed the river on a raft made of reeds and pieces of palm trunk.” (Budge 1907, 463)

“Sâî is a difficult place to reach, unless the traveller has his own boat with him. On January 2nd, 1821, Cailliaud crossed the river on a raft made of reeds and pieces of palm trunk.” (Budge 1907, 463) “Hoskins in June, 1832, needed no raft, for the water in the Western channel only came up to the camel’s knees, and he passed over to the island from the mainland without difficulty.” (Budge 1907, 463)

“Hoskins in June, 1832, needed no raft, for the water in the Western channel only came up to the camel’s knees, and he passed over to the island from the mainland without difficulty.” (Budge 1907, 463) “Burckhardt, who must have been there in the winter, could obtain the use of neither ferry nor raft, and was therefore obliged to abandon his projected visit.” (Budge 1907, 463)

“Burckhardt, who must have been there in the winter, could obtain the use of neither ferry nor raft, and was therefore obliged to abandon his projected visit.” (Budge 1907, 463) “On the following morning we had our boats loaded early, and dropped down the Nile with the current; as there was no wind we made good progress. In about two hours we sighted a mass of ruined walls which were built on the extreme edge of the Island of Sâî, close to the river. We found a convenient place on the bank and landed, and then climbed up a steep, rough path to the remains of what is called the “Castle of Sâî.”” (Budge 1907, 461)

“On the following morning we had our boats loaded early, and dropped down the Nile with the current; as there was no wind we made good progress. In about two hours we sighted a mass of ruined walls which were built on the extreme edge of the Island of Sâî, close to the river. We found a convenient place on the bank and landed, and then climbed up a steep, rough path to the remains of what is called the “Castle of Sâî.”” (Budge 1907, 461) Reference

Reference