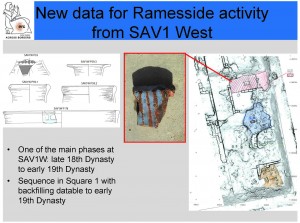

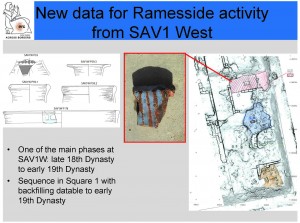

One of the most interesting results of the 2014 and 2015 field seasons on Sai is the presence of early Ramesside material within the town. A number of pottery sherds from SAV1 West are datable to the 19th Dynasty – among them there are examples of the famous Blue-painted ware.

Blue painted pottery is among the best known wares from Ancient Egypt. Its main characteristics are the blue colour, a large range of decorative, mostly floral motives, fancy shapes, a rather short lifespan (approximately 1430-1140 BC, from the mid-18th Dynasty until late Ramesside times). The key finding places of blue painted pottery are urban centres and capitals like Thebes, Memphis, Amarna and Gurob. New excavations at settlement and temple sites as well as in cemeteries and cultic centres (e.g. at Qantir, Saqqara, South Abydos, Umm el-Qaab, and Elephantine) have produced additional material that underscores a much broader distribution and also a great variability in use (cf. Budka 2008, Budka 2013).

Blue-painted sherds from SAV1 West chiefly feature linear patterns comparable to the material at Qantir (Aston 1998, 354-419) and can consequently be dated to the Ramesside period. They also find close parallels at Umm el-Qaab/Abydos and Elephantine, again originating from the 19th Dynasty (Budka 2013).

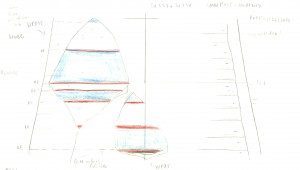

Fragments of an early 19th Dynasty blue-painted vessel from SAV1 W with linear decoration.

A particular interesting piece is a fragment from the shoulder (or neck?) of a large vessel – it was found in an area of Square 1 in SAV1 West, where we recorded a sequence of archaeological levels from the early 19th dynasty down to the mid-18th Dynasty.

The small fragment of a blue-painted amphora with vertical grooves and its context.

The blue-painted pottery fragment shows a special style of decoration: vertical grooves or the fluting of a zone around the neck and/or shoulder. This style is rare at Amarna (Rose 2007, 28-29), but well known from Ramesside contexts at Qantir (Aston 1998, 414), Saqqara, Thebes and Elephantine (Budka 2013). The famous amphora MFA 64.9 with applied decoration and a lid also falls into this group. Similar ornamental vessels were recently discovered at Elephantine.

All of the blue-painted fragments with fluting found in stratified contexts on Elephantine can be associated with the 19th Dynasty, most likely with the reigns of Seti I and Ramesses II. I would propose a similar date for the small fragment from Sai – this corresponds also to its stratigraphic find position in SAV1 West.

Future fieldwork in SAV1 West will hopefully help to contextualise this significant piece further.

References:

Aston 1998 = D.A. Aston, Die Keramik des Grabungsplatzes Q I. Teil 1, Corpus of Fabrics, Wares and Shapes (Forschungen in der Ramses-Stadt. Die Grabungen des Pelizaeus-Museums Hildesheim in Qantir-Pi-Ramesse 1), Mainz 1998.

Budka 2008 = J. Budka, VIII. Weihgefäße und Festkeramik des Neuen Reiches von Elephantine, in G. Dreyer et al., Stadt und Tempel von Elephantine, 33./34./35. Grabungsbericht, Mitteilungen des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts, Abteilung Kairo 64, 2008, 106–132.

Budka 2013 = J. Budka, Festival Pottery of New Kingdom Egypt: Three Case Studies, in Functional Aspects of Egyptian Ceramics within their Archaeological Context. Proceedings of a Conference held at the McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research, Cambridge, July 24th – July 25th, 2009, ed. by Bettina Bader & Mary F. Ownby, Orientalia Lovaniensia Analecta 217, Leuven 2013, 185–213

Rose 2007 = P. Rose, The Eighteenth Dynasty Pottery Corpus from Amarna, Egypt Exploration Society Excavation Memoir 83, London 2007.