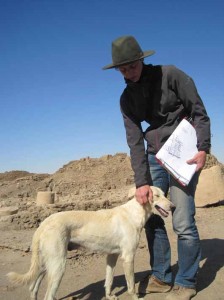

Even though we have already been back in Vienna for some time, I would like to give some information on the 3D-laserscanning campaign, which was carried out on SAI Island from February 3-10, 2014. Robert Kalasek from the Technical University of Vienna was the main person in charge of the scanning process, providing his know-how and years of practical experience in the field of 3D-laser scanning. My part was to provide technical and scientific assistance, letting the knowledge acquired from last year’s architectural survey flow into the work process.

The main goal of the work was to obtain a complete geometric documentation of the remaining walls and floors of the southern part of the New Kingdom town on Sai Island. 3D-laserscanning seemed to offer the most comprehensive result which could be achieved in a relatively short time.

For the scanning an Image Laser Scanner Riegl VZ-1000 was used, a Nikon D800 camera with a 14 mm lens was mounted on the scanner in order to record the texture. During the scanning process a grid of three dimensional points is automatically measured in the surveyed area by the instrument. So-called 3D point clouds result from this process, including xyz-coordinates and an intensity value depending on the surveyed material.

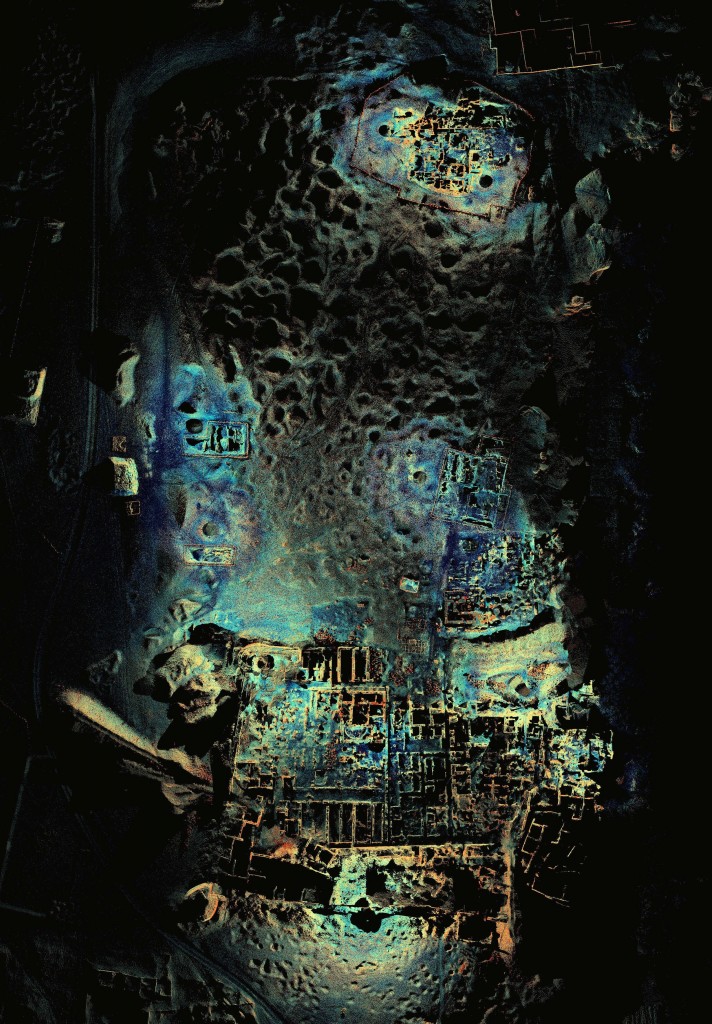

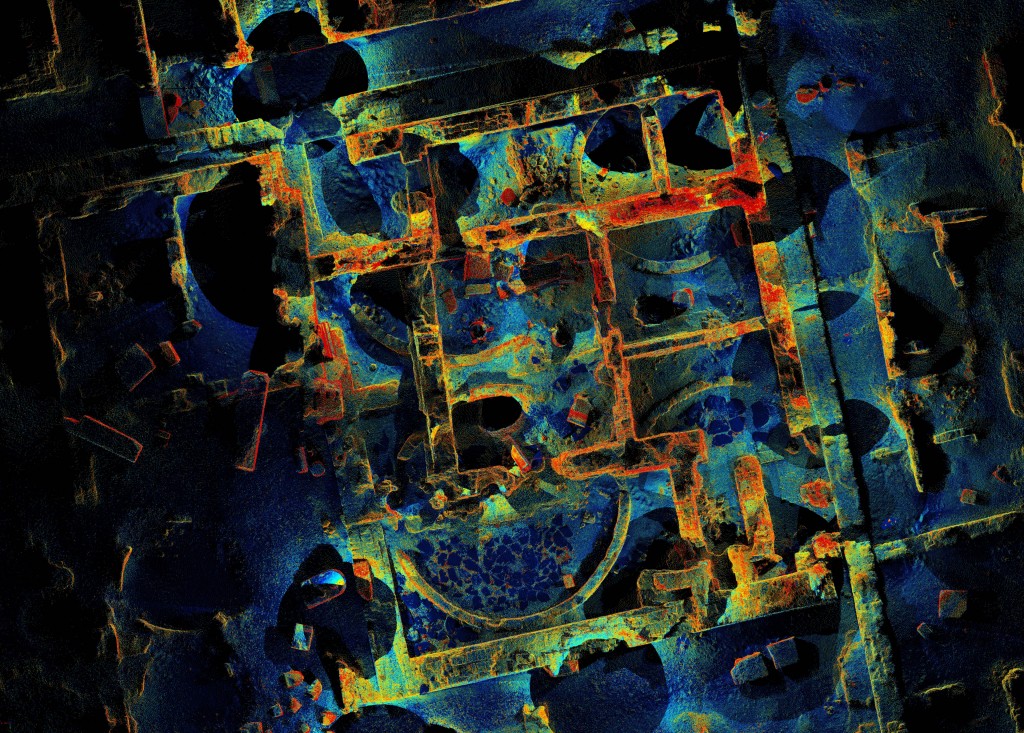

The complete scanning of the remains of the Pharaonic town required 155 different scan positions, whereby the maximum distance of the measured points ranged between 200 and 400 m, according to the angle of incidence and the reflectivity of the material. The result of each scan is a point cloud in a local coordinate system. In a next step, the scans can be joined (registered) with the help of a multitude of reflector points, which were distributed throughout the ruins. Generally, at least five overlapping points are needed in order to put two scans together. These reflector points were also measured with a total station so that the registered scans can be placed into a geo-referenced net. With the help of the intensity information one can encode the three dimensional point clouds with different colors, which is often sufficient to differentiate the various objects.

Scan of part of the storage rooms of the Pharaonic town with different colors for the intensity of the textures

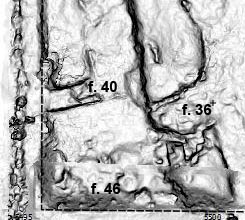

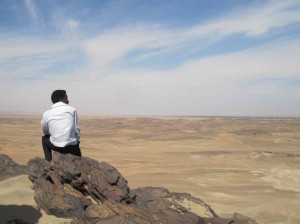

In addition to the standing remains of the Pharaonic town, the newly excavated trenches (SAV1 East and SAV1 West) as well as SAV1 North were also scanned and geo-referenced. In order to collect data for the topographic understanding of the surroundings, four long-range scans (range: 1.2 km) from elevated points were also undertaken. This could maybe help in understanding the general topography of the town and also to clarify questions such as the course of the city wall on the eastern side of the town.

Looking back on our days on Sai Island, I am happy to say that our campaign proved to be very successful and everything worked out as planned. Luckily, we had very few nimiti-days and the strong winds did not affect the stability of the scans as much as we had feared. The work-flow was very smooth and even though the work load was intense, especially for Robert, who worked on the data acquired during the day every evening until long into the night, we left Sudan with a lot of positive energy.

Next to the final registration of the scans, the post-processing in Vienna now entails the preparation of the data, e.g. reducing the enormous amount of data and refining the registration. The final output, a geometrically accurate three-dimensional model, can be used in the future to produce scaled plans and sections and a terrain model. It can also serve as a basis for further analyses and the creation of a reconstructed visualization of the Pharaonic town.