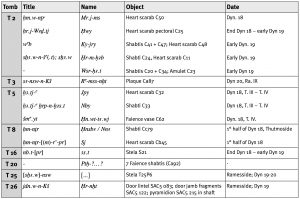

Prosopography is about people. With this phrase, I already began my last blog post assessing the social fabric of New Kingdom Sai as it becomes visible through the prosopographical data of its elite necropolis, SAC5. During the last field seasons, a new tomb, T 26, was discovered and excavated there (Budka 2015). At the bottom of its shaft, lintel and door jamb fragments as well as an inscribed sandstone pyramidion were found. The inscription on the latter artefact added another very important person to the prosopographical list of this cemetery: the deputy of Kush Hornakht. He was already known from four inscribed architectural elements coming from the Pharaonic town itself and two others found in Abri and Amara East (Fouquet 1975, Budka 2001, 210-212). Additionally, a door lintel fragment was quite recently discovered in a modern village on Sai showing him together with his wife (Budka 2015). This attestation adds another female entry to the Sai prosopographical list which is quite gender biased in favour of male members of the local society. This is, however, typical for Pharaonic Egypt and Sudan.

When we consider his archaeological monuments, it becomes clear that the deputy of Kush Hornakht had an office building or residence in the city centre of Sai and a monumental tomb with a pyramid at SAC5. This puts Sai back on the map for a certain administrative presence during Ramesside times, when a little further north at Amara West a new walled town was founded by Sethi I and substantially redeveloped under Ramses II that functioned as the seat of power for the administration of Kush (Spencer/Stevens/Binder 2015). Based on the limited geographical distribution of the monuments of Hornakht in the Amara-Abri-Sai region, Julia Budka has recently argued that Hornakht might be a local born on Sai, who was educated in Egypt and later send back to his hometown to fulfil his administrative duties as agent of the Pharaonic state (Budka 2015). He was, therefore, definitely a direct member of the local social fabric and of considerable social and functional standing. Accordingly, he also chose to be buried in the elite necropolis of his home town in a typical private New Kingdom pyramid tomb.

Hornakht is, however, not the only Ramesside deputy of Kush known from Sai. In 1843, Richard Lepsius came across two door jambs with the cartouche of Thutmosis III. Both had the subsequently added image of an official with his titles and name on their inside. They read “overseer of all priests of all gods” and “deputy of Kush Usermaatrenakht” (Lepsius 1913, 226). In 1954, a possible fragment of one of these door jambs could be recovered (Vercoutter 1956, 76). Based on his basilophorous name, Usermaatrenakht might also be considered an official of non-Egyptian descent (Nubian?) in the service of the Pharaonic state in Upper Nubia (cf. Schulman 1990). The presence of two Ramesside deputies of Kush on Sai is, therefore, of interest for understanding the social and political importance of the town in the 19th Dynasty in the region. At Amara West, however, several other individuals with the title of “deputy (of Kush)” are – next to viceroys and other local officials – known from the town and the cemetery (Spencer 1997; Spencer/Binder 2015). All these individuals equally attest to the particular prominence of Amara West in Ramesside times in the region and in Upper Nubia in general.

Bibliography:

Budka 2001: J. Budka, Der König an der Haustür. Die Rolle des ägyptischen Herrschers an dekorierten Türgewänden von Beamten im Neuen Reich, Veröffentlichungen der Institute für Afrikanistik und Ägyptologie der Universität Wien 94, Beiträge zur Ägyptologie 19, Wien.

Budka 2015: J. Budka, Ein Pyramidenfriedhof auf der Insel Sai, in: Sokar 31, 54-65.

Fouquet 1975: A. Fouquet, Deux Hauts-Fonctionnaire du Nouvel Empire en Haute-Nubie, in: CRIPEL 3, 127-140.

Lepsius 1913: K. R. Lepsius, Denkmäler aus Aegypten und Aethiopien. Text Bd. 5, hrsg. von Edouard Naville, bearbeitet von Walter Wreszinski, Leipzig.

Schulman 1990: A. R. Schulman, The Royal Butler Ramessesami’on. An Addendum, in: CdE, 65, 12-20.

Spencer 1997: P. Spencer, Amara West I. The architectural report, EES 63, London.

Spencer/Binder 2015: N. Spencer, M. Binder, Amara West 2015 (week 6): a familiar character appears. URL: https://blog.amarawest.britishmuseum.org/2015/02/21/amara-west-2015-week-6-a-familiar-character-appears/ (last accessed: July 4th, 2016).

Spencer/Stevens/Binder 2015: N. Spencer, A. Stevens & M. Binder, Amara West. Living in New Kingdom Nubia, London.

Vercoutter 1956: J. Vercoutter, New Egyptian texts from the Sudan, in: Kush 4, 66-82.