The second field season of AcrossBorders is approaching – tomorrow the first team members will already depart to Khartoum, travelling to Sai Island on December 31!

The second field season of AcrossBorders is approaching – tomorrow the first team members will already depart to Khartoum, travelling to Sai Island on December 31!

Our 2014 season is planned as six weeks of excavation and additional two weeks of studying finds and ceramics in the digging house. An international team of twenty scientists will come to Sai Island to investigate aspects of the New Kingdom town, working on various tasks and different areas. We will be supported by an inspector of NCAM – and we’re very happy that we have again the pleasure to work with Huda Magzoub! We will furthermore profit from the experience of our Rais Imad Mohammed Farah who will, like in the last years, supervise our Sudanese workmen.

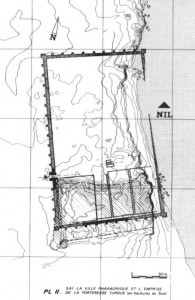

Compared to the initial season in 2013, we will go much further, in terms of excavation areas, methods and technology: A new excavation site with the name SAV1 West will be opened towards the west of the fortified town. One of the major aims is to test the structure and setting of the enclosure wall there. We hope to be able to provide a dating for the town wall; as yet it is based on the stratigraphical sequence and the corresponding ceramics found at SAV1North only. The question when exactly the Pharaonic site of Sai was surrounded by a mud brick fortification wall is of major importance to understand both the evolution of the site and its character as “temple town.”

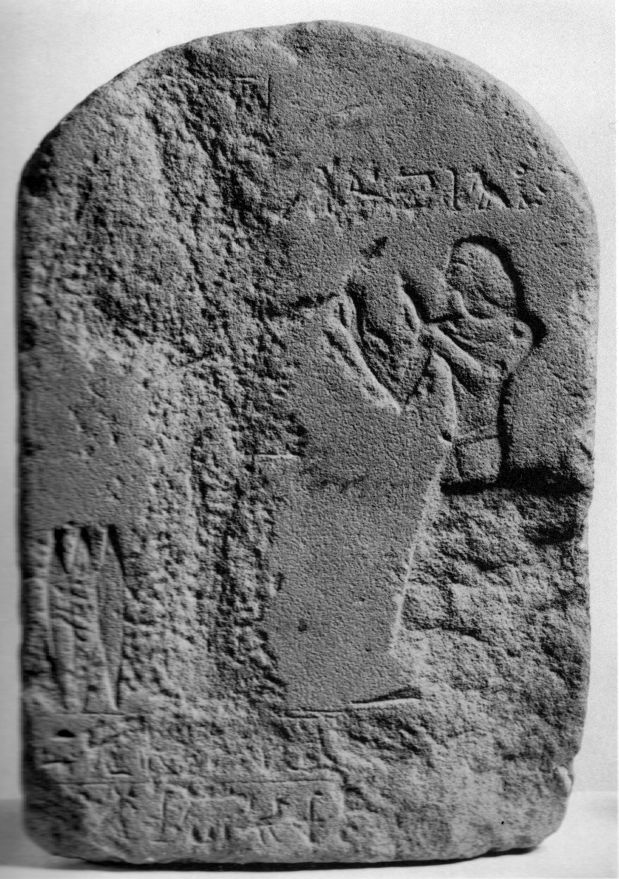

Overview of the as yet unexplored western part of the New Kingdom town, north of the Ottoman fortress.

Of course excavation at SAV1 East will continue – “building A” will be our focus and here especially its western part. Will we be able to confirm our preliminary interpretation of this building as administrative structure comparable to the so-called governor’s residence in the South?

2014 will also serve as testing phase for new documentation techniques – we will in particular use “structure from motion” and 3D applications, including a 3D laser scan of SAV1, thanks to cooperation with the Vienna University of Technology. Robert Kalasek from the Department of Spatial Planning of the Centre for Regional Science will conduct this laser scan, working closely with our architect Ingrid Adenstedt.

In addition, a geoarchaeological survey of the New Kingdom area will be undertaken by geologist Erich Draganits. For the first time, zooarchaeological remains excavated from the town area will be analysed in detail – Konstantina Saliari will focus especially on animals bones from SAV1North. Giulia d’Ercole will continue her studies on the petrography of the New Kingdom ceramics and will select new samples for both thin sections and iNAA. In particular we want to test more of the local, but also of the possibly imported Nile clays of the 18th Dynasty. Documentation of the small finds and tools as well as the pottery will be carried out simultaneously with the excavation. The architectural remains of SAV1 North will be investigated – Florence Doyen is coming for a last on site-check prior to her publication of this site within the New Kingdom town.

Last but not least, this year the “Sai Island Cultural Promotion” funded by the Qatar-Sudan Archaeological Project (QSAP) will start its work. First steps towards the planning of a site museum will be undertaken and several French experts will join us for this task.

A busy season is waiting for us – I have no doubts that it will be productive and highly interesting, thanks to all of the support by our Sudanese friends and colleagues and of course due to the joint efforts of all team members!