Pottery is very often used as evidence for trading and the distribution of goods. Information relating to trade networks can also be obtained from the New Kingdom material excavated on Sai Island.

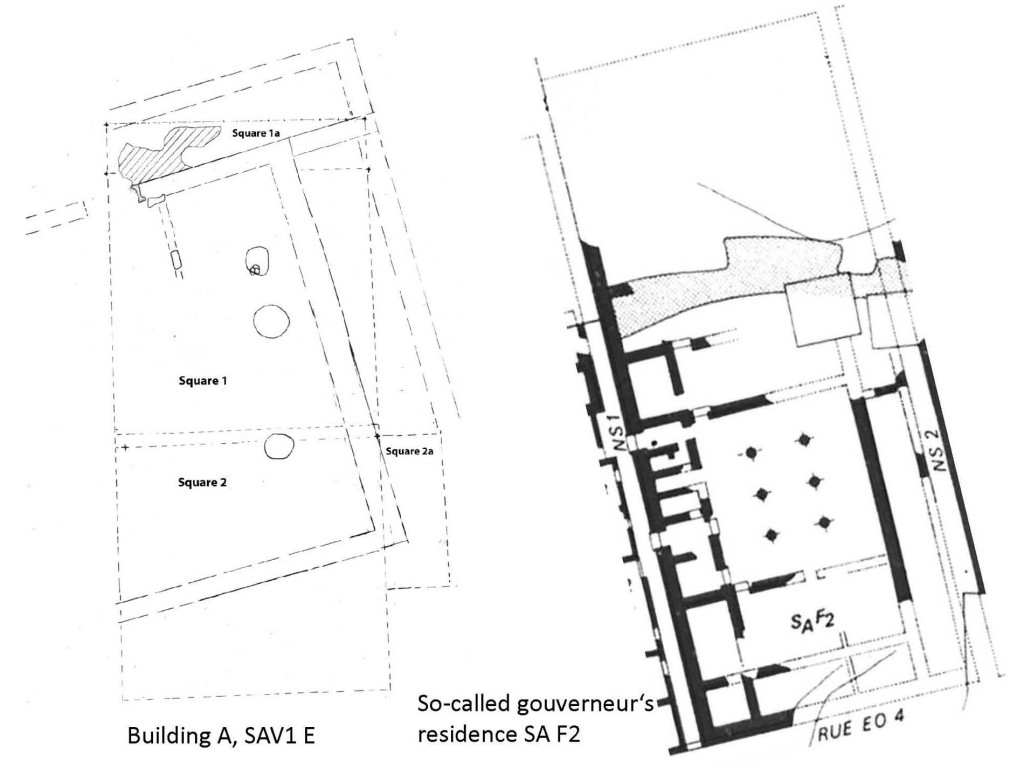

For Egypt, it is well known that the material culture of the 18th Dynasty – especially from the reign of Hatshepsut/Thutmose III onwards until the Amarna age – reflects an intense international transfer of goods and a common long-distance exchange of objects (cf. e.g. Brovarski, Doll & Freed 1982). This is obviously illustrated by the ceramics coming from SAV 1 North within the Pharaonic town of Sai – a number of Canaanite amphorae, painted Levantine jugs and jars, Pilgrim flasks of various origin, Cypriote vessels like Black Lustrous Wheel-made Ware and a fragment of a Mycenean stirrup jar (N/C 616) are especially noteworthy.

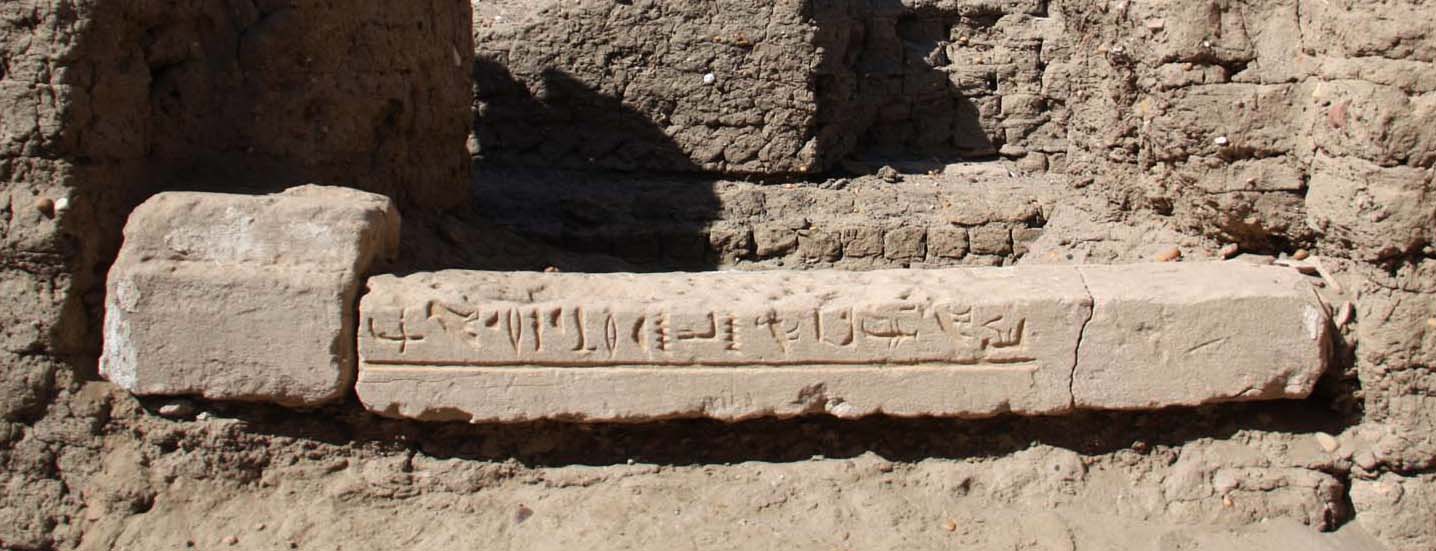

Fragment of a Mycenean stirrup jar from SAV1 North

These imported vessels show that Sai was fully integrated in the Egyptian trade network with the Eastern Mediterranean, at least from Thutmoside times onwards (Budka 2011, 31; Miellé 2011-12, 187). Besides the precious contents of imported vessels (especially oil and other essences), it is very likely that the vessels themselves held a value and were regarded as prestigious objects (cf. Seiler 2005, 49). They were often passed on for several generations and reused in different contexts, thus providing sometimes difficulties in dating as there might be a considerable difference between the production date and the date of deposition. From the Pharaonic town on Sai Island, several Canaanite amphorae sherds were for example reused as scrapers and for sure had a long lifespan.

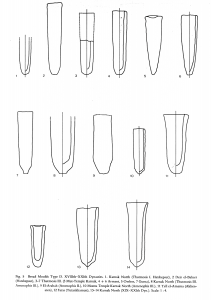

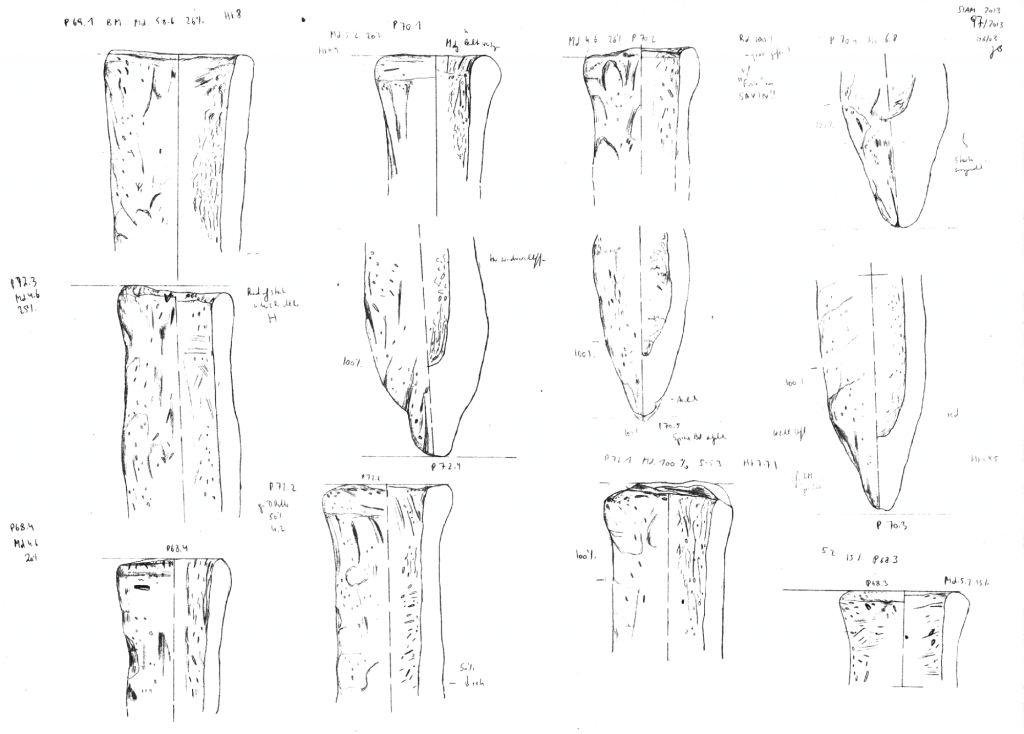

Imported vessels other than amphorae are primarily known from funerary contexts, being found as grave goods (cf. Hassler 2010) – as it is also the case on Sai Island. A complete Mycenean stirrup jar was discovered in tomb 21 in the major New Kingdom cemetery south of the town, SAC5. T21 61 is decorated with concentric circles and similar to types found at Amarna (cf. Hankey 1995) and Deir el-Medine (Minault-Gout/Thill 2012, 369, pl. 145, 161). Like in the case of N/C 616, there can be no doubt about the Mycenean origin of T21 61 – although Egyptian imitations of Aegean vases are well known from Egypt (Vermeule 1982), the Sai Island vessels are made in foreign fabrics. This is clear from a macroscopic investigation, but further proof is planned by scientific analyses for N/C 616, first of all by NAA.

In Nubia, Mycenean imports are in general rare (cf. Minault-Gout/Thill 2012, 369). A limited number of examples have been recorded in Lower Nubia, especially at Buhen and Aniba, and in Upper Nubia, for example during recent excavations at Tombos (Smith 2003, 152-154, fig. 6.21) and Amara West. The Mycenean stirrup jar from SAV1 North is one of the rare examples for such luxury vessels excavated in domestic contexts (see Hassler 2010, 211 for the primary use of stirrup jars in funerary contexts). It finds good parallels in the Egyptian town of Elephantine (material currently under study by the author) and gives evidence for the complex character of household pottery from Pharaonic settlements – a mixture including besides functional domestic types also painted and extraordinary pieces, most likely regarded as luxury items.

References:

Brovarski, E., Doll, S.K. & R.E. Freed (eds.) 1982: Egypt’s Golden Age: The Art of Living in the New Kingdom, Exhibition Catalogue, Boston.

Budka, J. 2011: The early New Kingdom at Sai Island: Preliminary results based on the pottery analysis (4th Season 2010), Sudan & Nubia 15, 23–33.

Hassler, A. 2010, Mykenische Keramik aus verlorenen Kontexten – Die Grabung L. Loats in Gurob, Egypt & Levant 20, 207–225.

Hankey, V. 1995: Stirrup Jars at El-Amarna, in W. V. Davies & L. Schofield (eds.), Egypt, the Aegean and the Levant. Interconnections in the Second Millennium BC, London, 116–124.

Miellé, L. 2011-2012: La céramique pharaonique de la ville fortifiée (SAV1 N) de l’île de Saï, CRIPEL 29, 173–187.

Minault-Gout, A./Thill, F. 2012: Saï II. Le cimetière des tombes hypogées du Nouvel Empire (SAC5), FIFAO 69, Cairo.

Seiler, A. 2005: Tradition & Wandel. Die Keramik als Spiegel der Kulturentwicklung in der Zweiten Zwischenzeit, SDAIK 32, Mainz am Rhein.

Smith, S. T. 2003: Wretched Kush. Ethnic identities and boundaries in Egypt’s Nubian Empire, London/New York.

Vermeule, E.T. 1982, Egyptian Imitations of Aegean Vases, in Brovarski, E., Doll, S.K. & R.E. Freed (eds.) 1982, 152–158.