From the end of January till the middle of March I joined the excavation on Sai Island, being responsible for drawing pottery and working on my M.A-thesis at Humboldt University Berlin with a very interesting object group as the subject: the so called “fire dogs”.

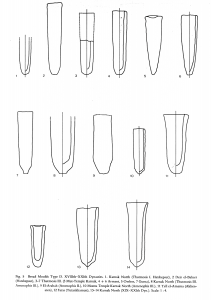

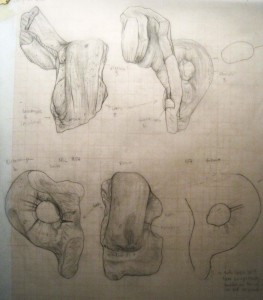

These pottery objects are in common scientific opinion described as a helping device for heating pots (see Aston 1989). The fortunate fact that a big number of “fire dogs” has been discovered in the Pharaonic town of Sai, offers a great opportunity understanding and evaluating these items more thoroughly. The basic outward appearance of a “fire dog” vessel is more or less a wheel made, bowl-like body with protruding elements like a handle or a knob at one side and mostly two “legs” or “ears” on top. In addition several pierced holes complete the look of the object.

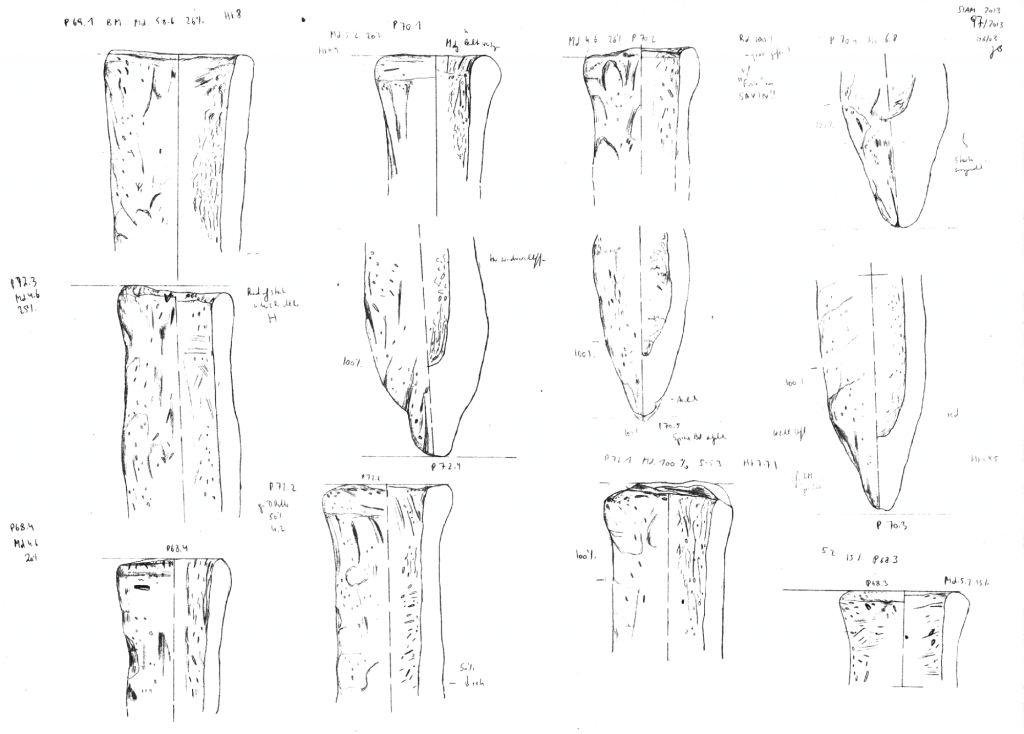

At the moment my corpus of “fire dogs” consists of 126 pieces – from small fragments of the ear right up to a few half preserved objects that give an impression of the overall shape. The “fire dogs” from Sai show a variety in size, the majority offers an impression of folded ears and in general burned parts can be recognized.

With the aid of the vast number of fragments, some interesting facts concerning the shape, function and manufacturing process can and will be figured out.

At present, at least two different production types are distinguishable:

a) The protruding elements are added to a massive, round body in form of a bowl. It seems as if the “ears” have been made out of a wrapped clay layer and then being attached to the body.

b) The body is constructed like a bowl-like vessel but then cut half in the middle. As a result, the two ears can be folded to the sites into the typical position. Therefore the overall shape of this type is probably made out of one piece and hollow inside.

More food for thoughts are the handles, which are added to a few examples instead of a knob. At one handle, some marks which resemble cuts can be discovered at the inside part of it. Another point is the sometimes very flat rim with small punctured impressions. Pamela J. Rose proposes for her examples from Amarna the idea that maybe the process of drying flattened the rim while the “fire dog” stood on it (Rose 2007, 50). However, not all “fire dogs” from the New Kingdom town of Sai provide this feature.

Especially the traces of use, like burning or abrasion, shall help identifying the function of this pottery type. At the moment some hints support the general assumption that “fire dogs” have been used to hold something over fire by standing on their 3 possible floor spaces (two legs and the knob or handle). In spite of that, there are also other examples that will need a new evaluation and explanation. A kind of multifunctional use within the object group seems likely.

During the 2013 season on Sai, I focused on collecting data, grouping the pieces, making drawings for documentation and taking photos of the objects. The next step here in Berlin is the analysis of the material in form of my M.A.-thesis. Still unanswered questions will hopefully find a solution by conclusive arguments based on the material from Sai and comparisons with other sites.

Besides all the scientific aspects I am very grateful to work with that material on my studies. It is a very nice opportunity for a student to get into contact with the “real” work of an archaeologist, having to make up one’s mind how to organize your “own project”. So all my thanks to Julia Budka and especially to the ancient inhabitants of Sai for this interesting left over from their past.

References:

Aston, D. A 1989: Ancient Egyptian “Fire Dogs” – A New Interpretation, MDAIK 45, 27–32.

Rose, P. J. 2007: The Eighteenth Dynasty pottery corpus from Amarna, EES Excavation Memoir 83, London.