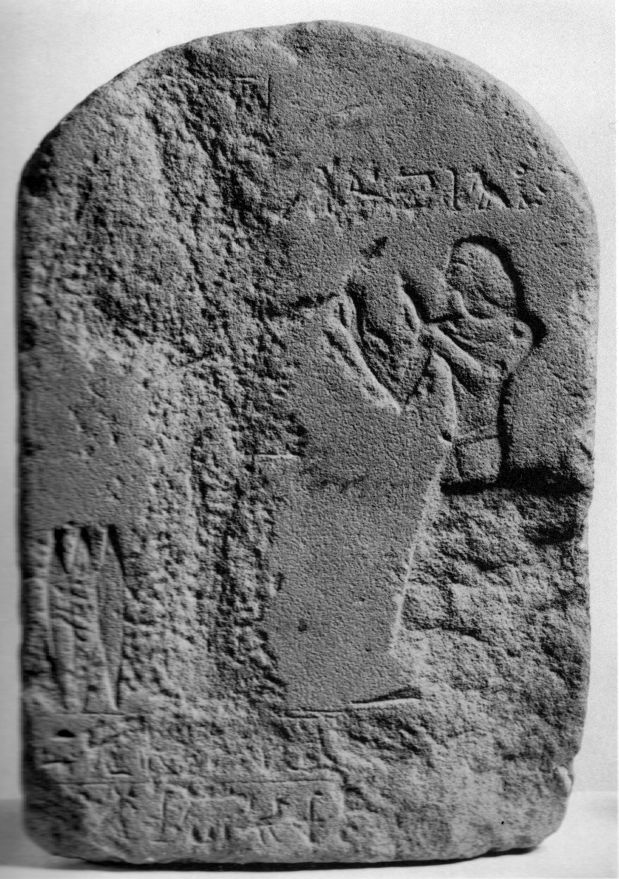

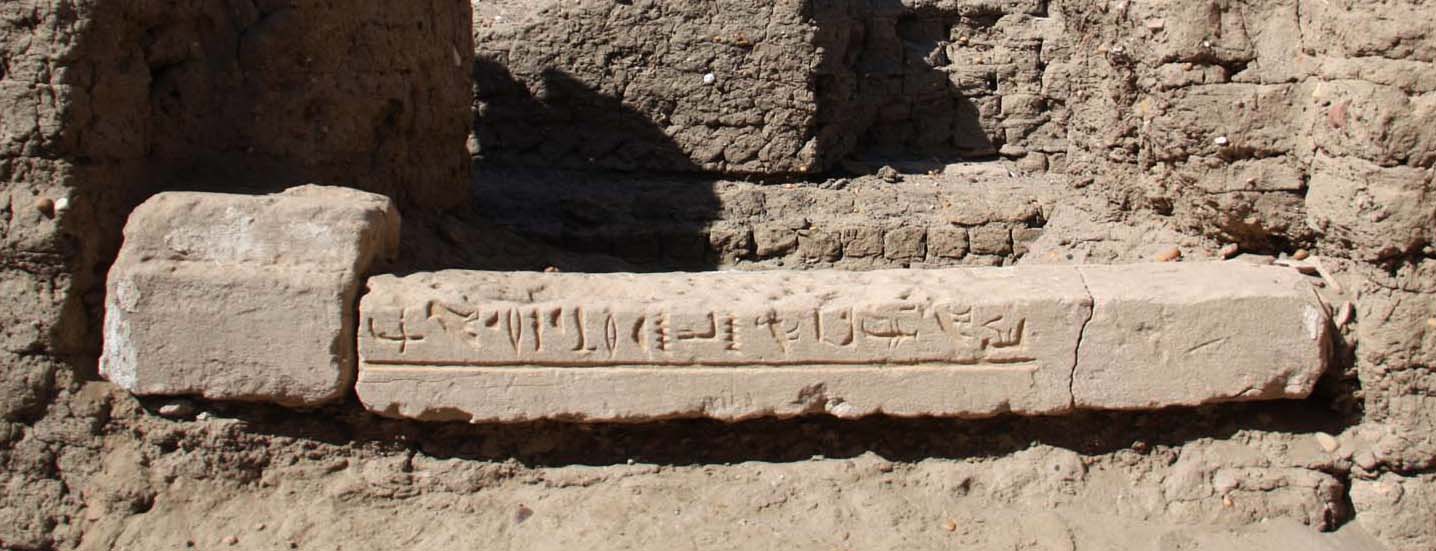

One of the highlights of this season at SAV1 West is a small fragment of a private sandstone stela, SAV1W 590. Unfortunately it is without proper archaeological context being a surface find which Martin Fera discovered south of Square 1, more or less in line with the town enclosure.

This interesting piece (10.6 x 11.2 cm with a width of 3.4 cm), the upper part of a round-topped small stela, was decorated in raised relief of quite good quality. The lunette shows the common motif of a so-called shen-ring flanked by two udjat eyes. Below the right udjat eye, facing left, the presumed donor of the stela is represented: He is wearing a shoulder long wig and is offering a libation to persons facing him. Only the lotus flower held by the first seated person on the left is preserved – it was probably a female family member, maybe the mother of the donor. However, in the 18th Dynasty the lotus as an attribute is also well attested for men. For example, a fragmented sandstone stela discovered in the elite New Kingdom cemetery at Sai shows a seated couple, with the man holding a lotus flower next to a woman embracing him (T16S21, see Minault-Gout/Thill 2012, Sai II, p. 162, p. 84).

This interesting piece (10.6 x 11.2 cm with a width of 3.4 cm), the upper part of a round-topped small stela, was decorated in raised relief of quite good quality. The lunette shows the common motif of a so-called shen-ring flanked by two udjat eyes. Below the right udjat eye, facing left, the presumed donor of the stela is represented: He is wearing a shoulder long wig and is offering a libation to persons facing him. Only the lotus flower held by the first seated person on the left is preserved – it was probably a female family member, maybe the mother of the donor. However, in the 18th Dynasty the lotus as an attribute is also well attested for men. For example, a fragmented sandstone stela discovered in the elite New Kingdom cemetery at Sai shows a seated couple, with the man holding a lotus flower next to a woman embracing him (T16S21, see Minault-Gout/Thill 2012, Sai II, p. 162, p. 84).

All in all, the upper part of our sandstone stela displays a scene commonly associated with funerary stelae – a son, taking the role of a funerary priest, offering to family members, in most cases to his deceased parents. A nice complete example of this general theme is the round-topped limestone stela British Museum EA 280.

According to the stylistic features of hair and costume of the donor, I would suggest the mid 18th Dynasty as most likely date for the stela from SAV1 West. Closely similar are representations of persons on stelae originating from the reigns of Thutmose III and especially Amenhotep II – for example the stela of viceroy Usersatet offering to Thoth, now in the British Museum (EA 623).

Regrettably, no text has survived on our piece identifying the offering person by name – we can safely assume that it was one of the officials working and living on Sai, and maybe even getting a tomb and burial here. What must remain open for now is whether the small stela from SAV1 West depicts an Egyptian official (born in Egypt and temporarly stationed in Nubia) or rather an “Egyptianized” family member of the elite indigenous clans who are known to have played an important role in Upper Nubia during the New Kingdom. The missing lower part of SAV1W 590 may have held some text and thus give additional information – maybe we will be lucky enough to relocate it next year!