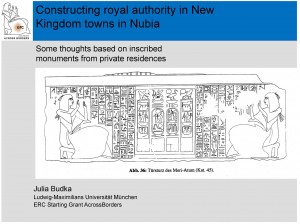

Prosopography is about people. This statement emphasises the importance of prosopography as a specific means of shedding light onto the social fabric and historical development of ancient and modern population groups. In our case, this society is the people of Sai during the New Kingdom. Prosopography in its broadest sense can be defined as “the investigation of the common background characteristics of a group of actors in history by means of a collective study of their lives” (Stone 1971). However, we can only tackle certain aspects of people’s lives using ‘prosopography’ due to the nature of the data from Pharaonic Egypt. Despite this shortcomings, what really matters are the questions we ask in order to understand lives and the social fabric based on prosopographical data. As for New Kingdom Sai, texts and monuments with names and titles of individuals from the island itself or with links to the Pharaonic town constitute the basis for a prosopographical ‘sociography’, i.e. an assessment and discussion of the social fabric of the town and its population.

Fig. 01

Cemeteries of Pharaonic towns in both Egypt and Nubia represent certain parts of the local society. Within the New Kingdom funerary landscape of Sai, that consists of three burial grounds (SAC1, SAC4 and SAC5; Fig. 01), it is only cemetery SAC5 that yielded texts and objects with prosopographical data (Minault-Gout/Thill 2012, esp. 403-418). Both the architecture of the tombs with chapels and pyramids and single or multi-chambered subterranean structures and the remains of the funerary object assemblages allow us to call SAC5 the elite necropolis of New Kingdom Sai. The question of whether the individuals interred here were ‘Egyptian’ or ‘Nubian’ is not of special concern for our endeavour. The fact, that they were buried here, is proof that they belonged to the local community regardless of their origin or ethnicity.

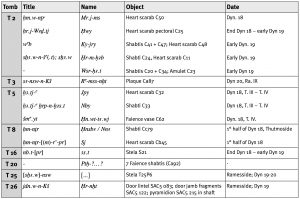

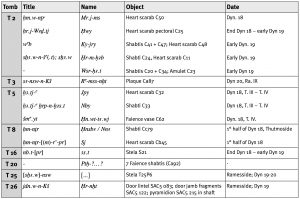

At present, 26 elite tombs are excavated at SAC5. An assessment of their archaeological as well as prosopographical ‘yield’ (Fig. 02) shows that the use life of this cemetery spans most of the New Kingdom from mid-18th Dynasty to later Ramesside and even beyond to Napatan times. The title and name-bearing small-finds among the funerary assemblages are the typical objects also found in other elite New Kingdom cemeteries in Nubia, especially shabtis, heart scarabs and heart scarab pectorals. Architectural elements from the tomb chapels and pyramids preserve information on the interred persons, too. In tomb T 2, five male members of the New Kingdom Sai society are attested. Three of them – Merimose, Hui and Ky-iri – are local priests, although there is no indication of the cult they were attached to. The letter-scribe Horemheb is part of the administrative sphere of the town responsible for its correspondence. The objects from tomb T 8 bear witness to two further local priests. In tomb T 3, an intriguing faience plaque with the name of Ramessesnakht, viceroy of Nubia under Ramesses IX, came to light. The burial with this sealing plaque is not considered to belong to the viceroy himself. It might rather belong to a local member of the late Ramesside administration of Nubia who was given this plaque as a token of loyalty during his lifetime. However, Ramessesnakht’s tomb is not known.

Fig. 02

Tomb 5 is of special importance for the upper end of the social fabric of the Pharaonic town. Based on the names and titles from a heart scarab, a shabti and a faience vase, it belonged to a family of local mayors. While the other tombs from SAC5 provided ‘only’ scribes and priests, we encounter here the highest municipal representatives of Pharaonic state agency in New Kingdom Sai, the city governors Ipy and Neby. Both date to the mid-18th Dynasty and might be father and son, since the mayoral office is regularly transmitted like this in the New Kingdom. The exact familial relation of the songstress Henut-aat (or Henut-taui) to both Ipy and Neby is unclear. Her title, however, puts her in a rather high female elite stratum as well. One of the tomb owners, Neby, even seems to be identical with the mayor and director Neby attested further north at the Tanjur rapids in the Batn el-Hajar with three rock inscriptions (Hintze/Reineke 1989, 170-177; Fig. 03 after Hintze/Reineke 1989, 235). His territorial radius even went well beyond the confines of the town.

Fig. 03

Mayors or city governors are typical for all New Kingdom towns and cities in Egypt and Nubia. A recent assessment of the distribution of New Kingdom mayoral tombs has shown, that they are in most cases buried in the elite necropoleis of the city which they administered (Auenmüller 2011; Fig. 04). This typological trait can also be seen with Ipy and Neby and their interment in tomb 5 at SAC5. However, there is another mid-18th Dynasty mayor of Sai attested. This Ahmose installed two statues of himself at Thebes (Bologna KS 1823) and Karnak (CG 42047) respectively. Both statues indicate his special relations to Thebes or even a Theban origin. He therefore might be the first mayor of the newly established colonial town, sent to Sai under Thutmose III. Although Ahmose’s tomb is not known, it is generally assumed that his funeral took place at Thebes, his home town and place of belonging. By contrast, Ipy and Neby seem to represent the second generation of local administrators who lived on Sai for some time, identified themselves with the town, were parts of its social fabric and finally chose to be buried here.

Fig. 04

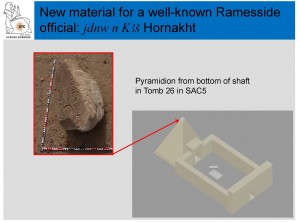

Further titles and names are attested through funerary stelae and shabtis. However, due to the rather fragmented state they are less informative. They nevertheless show that SAC5 in its original state must have been a very well equipped funerary landscape for the local elite. This was further stressed by AcrossBorders’ discovery of a new tomb, tomb T 26 (Budka 2015). This new monument yielded the pyramidion of a very important person: the deputy of Kush Hornakht, who flourished in the 19th Dynasty. He and his elite colleagues that are also – or especially – known from the area of the town will be subject of some future blog posts.

A summarising look back at the Sai SAC5 prosopography allows for some comments: Although the data is quite fragmented, it displays both religious and administrative personnel of the town. Both domains, temple and administration, are typically represented by officials in New Kingdom town cemeteries in Egypt and Nubia (cf. esp. Soleb: Schiff-Giorgini 1971). Of high importance for and within the town’s social fabric are the two 18th Dynasty mayors Ipy and Neby. They belonged to the Egyptian elite that came or was sent south to Nubia to act as municipal agents of the Pharaonic state on Sai. Exceptional, however, is the attestation of the deputy of Kush Hornakht, who we know was active in the 19th Dynasty. His person provokes further thoughts on the role of Sai as administrative centre and urban fabric in Upper Nubia during Ramesside times.

Bibliography:

Auenmüller 2011: J. Auenmüller, Individuum – Gruppe – Gesellschaft – Raum. Raumsoziologische Perspektivierungen einiger (provinzieller) HA.tj-a Bürgermeister des Neuen Reiches, in: G. Neunert, K. Gabler & A. Verbovsek (eds.), Sozialisationen: Individuum – Gruppe – Gesellschaft, GOF IV/51, Wiesbaden 2011, 17-32.

Budka 2015: J. Budka, Ein Pyramidenfriedhof auf der Insel Sai, in: Sokar 31, 2015, 54-65.

Hintze/Reineke 1989: F. Hintze & W. F. Reineke, Felsinschriften aus dem sudanesischen Nubien, Publikation der Nubien-Expedition 1961-1963, Band 1, Berlin 1989.

Minault-Gout/Thill 2012: A. Minault-Gout & F. Thill. Sai II. Le cimetière des tombes hypogées du Nouvel Empire SAC5, FIFAO 69, Cairo 2012.

Schiff-Giorgini 1971: M. Schiff-Giorgini, Soleb II. Les necropoles, Florence 1971.

Stone 1971: L. Stone, Prosopography, in: Daedalus 100, No. 1, 1971, 46-79.