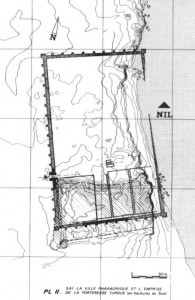

It is a well-established fact that the Pharaonic town of Sai with its fortified town, temple and administrative buildings falls into the category of so-called Egyptian “temple towns”, built during the New Kingdom in Nubia. The substantial mud brick enclosure wall of Sai with a width of more than 4.20 m has been investigated by the late Michel Azim (Azim 1975) in the South and Florence Doyen in the North (cf. Doyen 2009). As was confirmed in both sectors, the wall is equipped with bastions in regular distances. Our current work at SAV1 West aims to deepen the understanding of the layout, outline and construction of the enclosure wall as well as its building phases and periods of destruction.

At the moment – and this is all work in progress! – we were able to expose the outline of the western enclosure wall in the trenches 1 and 2. Its location fits perfectly to what Azim reconstructed as the western border of the Pharaonic town. However, there are still a lot of open questions – especially because of later disturbances and pits, but also due to several building phases within the brick work. In trench 2 we might have encountered a late sub-circular structure of possible Ottoman date, set into the 18th Dynasty enclosure wall. We will try to clarify this next week.

Western half of Square 1 (left) and Square 1W (right) at SAV1 West – overview towards South (Photo: Martin Fera).

In the southwestern corner of Square 1, the upper part of the enclosure wall as we exposed it so far is still covered with debris; a large pit filled with mostly Christian pottery was cutting into this area. Similar holes have been dug into the brick work of the enclosure wall at SAV1 North (see Doyen 2009). As was already observed by Azim in the 1970s, the Sai New Kingdom fortification suffered from several destructions, but also restoration phases during its use-life (Azim 1975, 122). A good example of a restoration is the tower construction N2 at SAV1 North which is maybe of Ramesside date (Doyen 2009).

A later addition to the western outline of the 18th Dynasty wall is now also traceable with our extension towards the west, Square 1W. Within this trench we also located a possible “front wall”, of which we as yet only reached the upper part. It seems as if a secondary construction was set between the New Kingdom brick work – spanning the area from the presumed front wall and the enclosure wall. A layer holding much organic material, charcoal and pottery of a domestic character may indicate that we have found here a small occupation spot, maybe a modest hut or shelter. Its date remains to be established but the pottery points to a Late Christian origin. However, it is intriguing that we also have some Ramesside sherds coming from Square 1W and the western half of Square 1 – comparing nicely to the findings around the tower at SAV1 North. At present, we cannot rule out that our squares are set above one of the bastions of the enclosure wall, maybe following complex building phases – all of this remains to be investigated during the upcoming three weeks of fieldwork at SAV1 West.

References:

Azim 1975 = M. Azim, Quatre campagnes de fouilles sur la Forteresse de Saï, 1970-1973. 1ère partie: l’installation pharaonique, CRIPEL 3, 1975, 1–125.

Doyen 2009 = F. Doyen, The New Kingdom Town on Sai Island (Northern Sudan), Sudan & Nubia 13, 2009, 17–20.