Working on Egyptian and Nubian cooking pots, both in the field and back home in Munich, Julia Budka and Daniela Penzer—who wrote her Masters thesis about Egyptian cooking pots earlier this year—created another practical session for the LMU students this summer.

Dealing with Egyptian and Nubian cooking pots during the production of our drawings doesn’t give us the opportunity to understand the process of cooking with them. There are lots of questions following our studies of these pots: First, it is necessary to understand how the pot was made. Second, it is useful to think about ways to combine the theoretical aspects of pottery making with practical exercises. Finally, the essential task would be to cook in replicas under more or less similar conditions as had been done in ancient times. The keyword here is experimental archaeology.

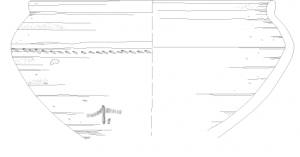

Within the practical class, a poster was prepared to illustrate the fundamental changes in cooking pot tradition at the beginning and throughout the 18th Dynasty (see Budka 2016). While texts and paintings give us a good overview regarding funerary practices and traditions, cooking is underrepresented in the reliefs and tomb decoration. Without a theoretical background, someone can just suggest why one shape of cooking pot was replaced with another one, and so experimental studies can provide us with useful information, which cannot be produced by the archaeological context alone. Also, the difference in cooking in Nubian cooking pots compared to Egyptian ones can be investigated further, maybe leading to interesting conclusions about diet and the cooking process. To create as much useful data as possible, the main tasks for the upcoming experiments won’t only be cooking in the pots, but to observe the different effects of distinctive temperature during the fire process and the permeability of water caused by the composition of the pots. Measuring temperature and heat will be crucial for significant results.

The experiments took again place in Asparn/Zaya in Austria – like Julia’s former experiments with fire dogs and other tasks and only possible because of Julia’s cooperation with the University of Vienna, from June 30th until July 2nd. We began our work by preparing the clay after Hans Reschreiter, field director of the famous Austrian excavations in Hallstatt, gave a nice introduction to the clay we used. The first task was to grind the clay with simple methods, such as using a stone or wooden tool.

The dry and dusty powder was then mixed with water before kneading. We grogged the clay with a measured amount of animal dung (e.g. donkey dung, cow, and goat dung, etc.), which Julia had brought from Sudan especially for experiments like this. However, another chunk of clay was simply grogged with chaff. Shortly after producing enough clay to work with we immediately started modelling our first small pots and dishes.

The progress of this work was nice to watch. Vera and Vig Albustin, both very experienced experimental potters (who joined AcrossBorders already at the fire dog experiment in 2014), showed us different ways to build the pottery by hand and using different shaping methods such as “paddle and anvil” or the “coiling-technique” (see Arnold/Bourriau 1993 for more details).

Step two (also under the guidance of Vera and Vig, who made realistic replicas of Nubian and Egyptian cooking pots before the actual excursion) was the process of firing the pottery in an open fire place.

On our second day, we continued with shaping different pots and dishes and began with the preparation of our experiment. The firing process of the pots was completed and everything ready for the main task on day three: experimental cooking in Egyptian style cooking pots.

First, we decided to arrange two cooking pots directly over a fire. We arranged the smaller pot over a triplet of stones and filled it with 2 litres of water. Additionally, a bigger pot was placed over fire dogs and filled with 5 litres of water.

Daniela was equipped with an infrared-thermometer in order to test the temperature of the blaze and fire; the outside temperature of the pot and also the temperature of the water periodically.

The purpose of this experiment was to check the time it took for the water to reach boiling point. Meanwhile, we had to continuously take care of the fire, which was sometimes not easy given that one of the pots was arranged over three stones.

After this first attempt to get some useful data, we prepared our lunch: Egyptian style “foul”. Daniela brought the ingredients: oil, onion, tomatoes, garlic and (canned) foul beans. Following the instructions in the recipe, Daniela again checked the temperature with the thermometer while cooking in our two pots; one over the stones and the second with AcrossBorders’ nice fire dogs.

The result of our cooking was quite delicious, with everybody enjoying the lunch break. Back in Munich, Daniela will be busy with interpreting the data and following up the experiments we performed.

To sum up, it is easy to say that the experience of working with clay, preparing it, producing small pots, and to perform the firing process was useful when you’re working with pottery on the project. It was a nice opportunity to perform different shaping methods with your own hands and to learn how to dry and then fire the pots. Everybody would therefore recommend that experimental archaeology is a perfect way to understand the subject of your research in more detail. Additionally, doing it as a team was also quite fun!

References

Arnold/Bourriau 1993 = Dorothea Arnold/Janine Bourriau (eds), An Introduction to Ancient Egyptian Pottery, Mainz am Rhein 1993

Budka 2016 = Julia Budka, Egyptian cooking pots from the Pharaonic town of Sai Island, Nubia, Bulletin de liaison de la céramique égyptienne 26, 285‒295.