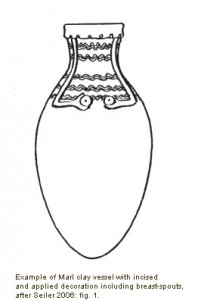

Time really goes by… not just for us but also for our dear ceramic samples. Not too long ago they were still hidden under the warm sun of Sudan in the nice setting of Sai Island. Since then, they have passed through the hands of different people and they have been – in turn – been photographed, drawn, recorded in our File Maker database and, finally, selected for the different laboratory analysis.

oakley gas can sunglasses

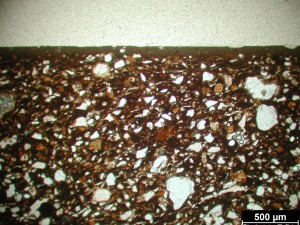

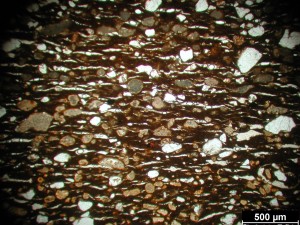

At the end of July, thanks to our cooperation with the Departments of Lithospheric Research and of Geodynamics and Sedimentology and the great work done by Claudia Beybel at the ‘Dünnschlifflabor’, we successfully managed to conclude the preparation of the thin sections for a first group of 36 ceramics. Just today, we submitted the second group of 24 samples to the lab – so we will have a total of 60 thin sections for petrographic studies.

After the summer break, the first group of samples were taken to the Institute of Atomic and Subatomic Physics (AI) for the Neutron Activation Analysis. Johannes Sterba, Ing.Dr. will be my scientific supervisor at the AI, introducing me to the wonderful world of INAA. He has not only a lot of experience in NAA and chemical analyses on ceramic materials, but also in working with archaeologists and ceramics from Egypt and the Levant.

ray ban sunglasses outlet

Under his supervision, I have prepared all the samples and on Friday August 23 Johannes put them in the machine ‒ so by the end of September we will hopefully have the first results! Waiting for them, I will share some of my experience about the preparation of the samples, illustrated by pictures taken in the lab.

Step 1 – Sampling strategy

One of the main advantages of INAA is that you need only very few grams of powder for each sample!

For most of our ceramic samples we just selected the small chips produced after the break for the thin section and ground them in an agate mortar to obtain a fine and homogeneous powder. This procedure takes only few minutes, but then you have to clean carefully both the mortar and the pestle in order to avoid any contamination between the samples (and an agate mortar can be quite heavy to hold and to carry…).

Seven potsherds were sampled by drilling, carefully avoiding the slip and/or the painting!

The obtained powder is temporarily collected in small plastic containers.

Step 2 – Weighing the powder

After one night in the oven at 90 °C, the sample is weighted by means of a precision balance (we need about 100 mg of powder) and transferred into pure silica vials. Both the vials and the spoon used for this operation are very small and thin. This is a good training both for your nerves and your hands (better not drink too much coffee before!)

Step 3 – Sealing the vials by fire

Before going into the reactor and to be irradiated, all the vials must be sealed. This operation is quite delicate and, at the same time, extremely important: poor seals will cause samples to open during irradiation! The sealing is made by fire, using a soldering iron arrangement in the same laboratory in which the samples were prepared. Once finished, we used an engraving tool to write the number of the sample on the side of each vial.

At this point everything is ready to start with the irradiation… just the time for our small samples to ‘rest’ a little bit immersed into a pure water solution!