In some respect I am very old-fashioned when it comes to analysing pottery – for example, I am still a big fan of organising a preliminary corpus of shapes on paper, with the copied drawings! It nice to have all of them together on a table and arranging them into groups, with the big advantage to simple add pieces or rearrange them differently.

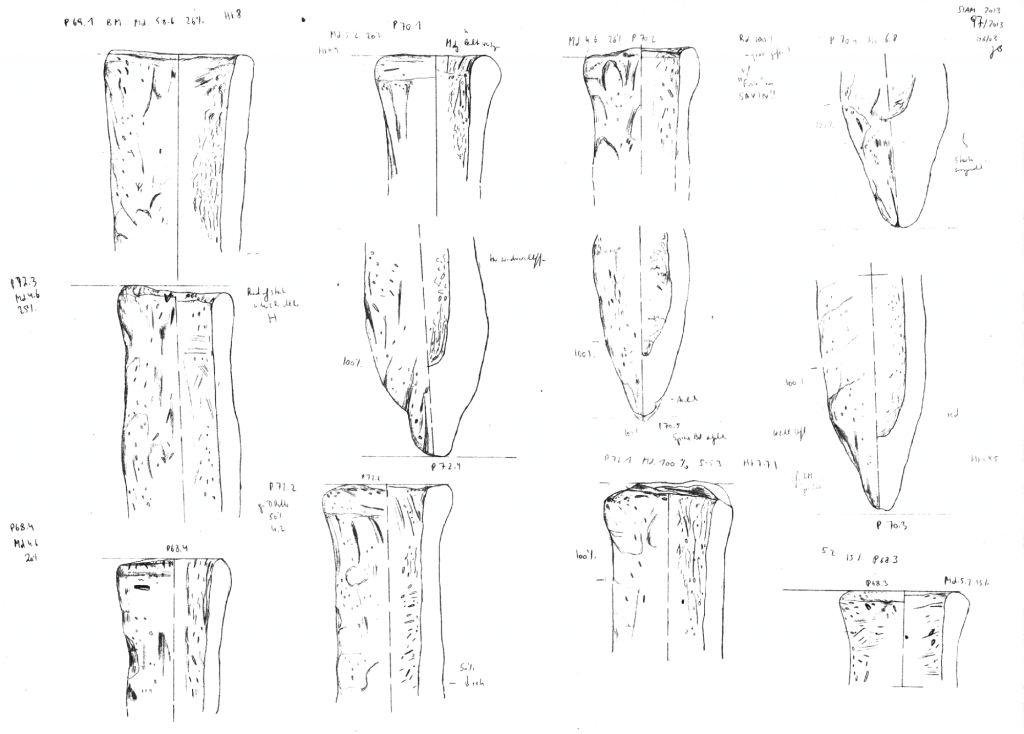

Over 800 pencil drawings from 3 field seasons at Sai Island (2011-2013) have been quite a challenge for Daniela the last weeks – after the heroic accomplishment of copying all the drawings, she is now using the spaciousness of our nice office to deal with the arrangement of the copied pieces.

This old-fashioned but effective mode of arranging pottery drawings according to shapes and ware groups goes back to my training at Elephantine – first supervised by Dietrich Raue, helping with his Old Kingdom material and later adapting it to my New Kingdom material. At Elephantine, one of the prime considerations was to have a back-up copy of all drawings in the dig house.

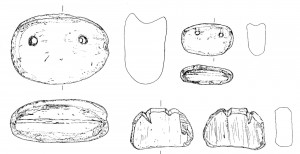

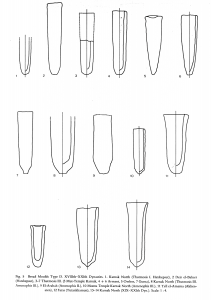

Samples of paper copies of pottery drawings from Elephantine: fragments of decorated marl clay vessels.

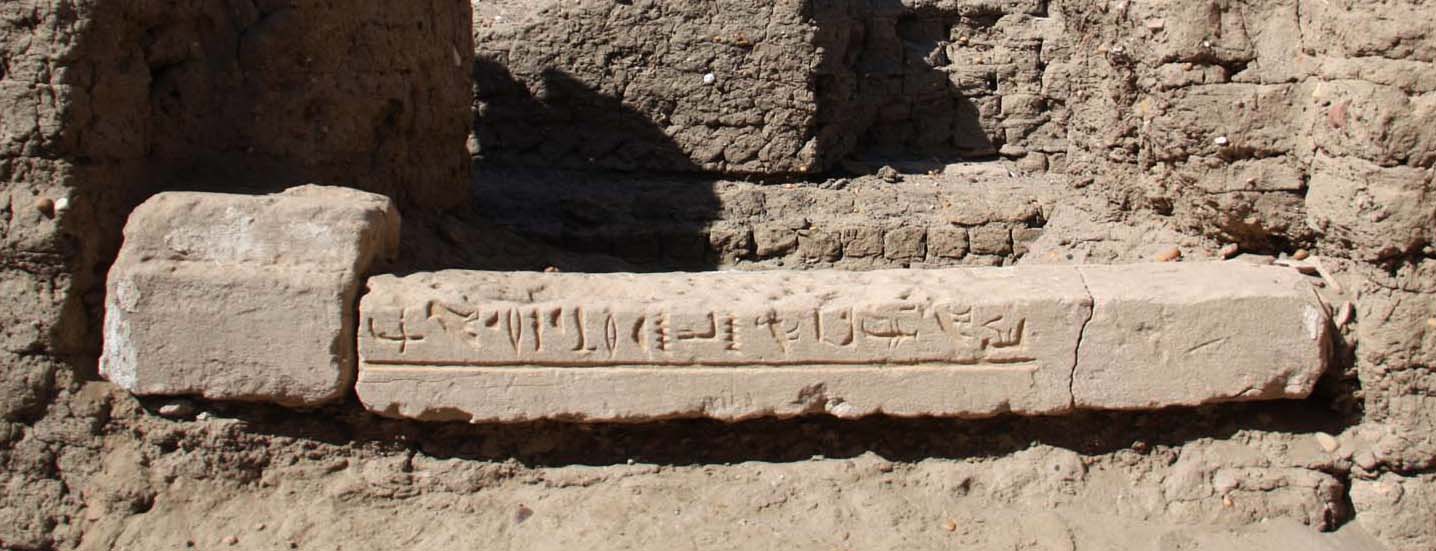

A nice group of decorated vessels from mid 18th Dynasty contexts at Elephantine provides good parallels for sherds from the New Kingdom Town of Sai Island. Marl clay bottles with a long neck are painted either in red and black, in red, black and blue, or in black only. The motifs comprise simple linear designs as well as floral and faunal elements (e.g. flowers, lotus buds, ducks and papyrus). The as-yet published parallels are dated to the reigns of Amenhotep II to Thutmose IV (see especially Hope 1987, 108–109 and 116), which corresponds well with the stratigraphic evidence at Elephantine (see Budka 2010) and also the findings from Sai. On the basis of the parallels, a Theban provenience has been proposed for the decorated vessels found at Elephantine – and this seems also very likely for Sai. We will address this issue of provenience in the upcoming years by means of scientific analysis, especially with Neutron Activation Analysis and XRF, hopefully providing more information about the contacts and exchange of wares and pots between Upper Egypt and Upper Nubia.

References

Budka 2010 = J. Budka, The New Kingdom-Pottery from Elephantine, in D. Raue, C. von Pilgrim, P. Kopp, F. Arnold, M. Bommas, J. Budka, M. Schultz, J. Gresky, A. Kozak and St. J. Seidlmayer, Report on the 37th season of excavation and restoration on the island of Elephantine, Annales du Service des Antiquités de l’Égypte 84, 2010, 350-352.

Hope 1987= C. A. Hope, Innovation and Decoration of Ceramics in the Mid-18th Dynasty, CCÉ 1, 1987, 97-122.