The 7. Tagung zur Königsideologie last week in Prague was perfectly organized and very interesting! Nubia was not the focus of the conference, but I learned a lot from a number of papers and enjoyed the discussion of various aspects of kingship and authority. I will continue to work on my proposed development of Sai Island in the 18th Dynasty, with a distinct change during the reign of Thutmose III/Amenhotep II noticeable in the architecture and the material culture as well as the textual evidence. Some aspects I did already mention in Prague will be further explained next week in London at the forthcoming colloquium at the British Museum “Nubia in the New Kingdom” – we’ll keep you posted!

Category Archives: Material Culture

The pottery samples: materials and methods

The ceramic samples for the archaeometric analyses comprise by now sixty-one sherds selected during the last field season from both sectors SAV 1North (48 samples) and SAV 1East (13 samples) of Sai Island New Kingdom Town.

All of the sherds have been classified according to their macroscopic features and these data were collected in the File Maker Database of the project.

In addition, prior to proceeding with the laboratory analyses, we took photographs of both the surfaces and sections of each sample. The samples are labelled with a new code: the acronym “SAV/S” (= “Sai Island New Kingdom Town/Sample”) followed by a progressive number, starting from SAV/S 01, and linked to the original ceramic number as recorded in the pottery database.

http://www.nikefreerunshoesplus.com nike free mary jane

The samples from both SAV 1North and SAV 1 East come from distinct areas, structures and layers of the archaeological deposit. They include different kinds of wares and shapes representing the variability of the pottery corpus. Among others, ceramics comprise Nubian beakers and cooking pots, Egyptian Nile silt wares (dishes, bowls, bread plates and bread moulds), Marl clay jars and imported amphora from both Canaan and the Egyptian oases.

http://www.nikefreerunshoesplus.com kids nike free

Forthcoming petrographic and chemical analyses will help us discriminating between these different samples and answering very important archaeological questions concerning the provenience, the technology of production, as well as the geographical distribution of these ceramics.

Net weights and fishing

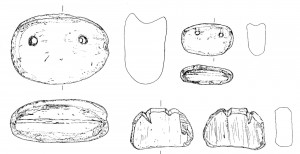

Fishing played obviously a role in daily life at Sai Island, also during the 18th Dynasty. A number of clay net weights, Egyptian in character, attest to local fishing by the occupants – at our new excavation area SAV1E just two net weights have been found in 2013; 20 more pieces have been documented at SAV1N between 2008 and 2012.

This type of weight for fishing nets is well known from Middle Kingdom models found in Egyptian tombs; corresponding artefacts have been documented at major fortresses in Lower Nubia like Buhen and Askut, sites which flourished in the Middle Kingdom (see Smith 2003, 1010). Large variants of such clay net weights with two perforations, resembling the shape of axe-heads, have been dated to the Middle Kingdom. At Sai Island, the size of the objects may vary from very small to middle and large within New Kingdom contexts and such a dating might therefore require a reassessment or at least a site specific chronology. Besides the “axe-head”-type, net weights appear also as re-cut sherds at SAV1N.

Elephantine provides contemporaneous parallels for both types of net weights from the Pharaonic town on Sai Island. von Pilgrim 1996 has classified the “axe-head” version as type A and re-cut sherds as type C. Interestingly, the distribution of the specific types of weights differs notably between Elephantine and Sai Island. For Level 10 at Elephantine, which is contemporaneous to Level 4 and partly Level 3 at SAV1N, 75.9 % of the net weights are type C (re-cut sherds) and 24.1 % type A (clay object with perforations) (von Pilgrim 1996, 279, fig. 123). The evidence from SAV1N is almost reversed: 17 weights are of von Pilgrim’s type A (= 85 %) and only three (15 %) of type C. Both examples from SAV1E are belonging to type A, thus supporting the dominance of this type of gear on the island.

This notable difference regarding the net weights from 18th Dynasty contexts at Sai Island and Elephantine remains to be investigated in the future. Could it be just an accidental finding, due to the still very small number of weights from Sai? Or might it reflect differences between the fishing gear in Egypt and Upper Nubia? Maybe the Middle Kingdom “axe-head” type was more popular and longer in use in Nubia than in Egypt. von Pilgrim has also proposed that type C at Elephantine, recycled from pottery sherds, is the cheap and ad hoc product for individual needs (von Pilgrim 1996a, 275–278). One could therefore speculate whether the distribution of net weights at Sai was primarily organized at a higher level. Type A might have been imported to Sai from Egypt and fulfilled the local demand for the most part. The need for an ad hoc production of type C would have been consequently less common than at Elephantine. Such a “centralized system of food production” as a reflection of the use of net weights of type A was already suggested by Smith for the Middle Kingdom phase at Askut (Smith 2003, 101). However, as we still do not know the size of the community living on Sai during the New Kingdom, any thoughts about demands and strategies for food production must remain very tentative for now.

References:

von Pilgrim 1996 = C. von Pilgrim, Elephantine XVIII. Untersuchungen in der Stadt des Mittleren Reiches und des Zweiten Zwischenzeit, AV 91, Mainz am Rhein 1996.

Smith 2003 = St. T. Smith, Wretched Kush. Ethnic identities and boundaries in Egypt’s Nubian Empire, London and New York 2003.

Reuse of pottery sherds from SAV1E

The reuse of pottery vessels or individual sherds for various purposes is a very common phenomenon throughout the ages and cultures – evidence for material-saving recycling processes in antiquity (see Peña 2007). Re-cut pot sherds as tools with multiple functions are frequently found at New Kingdom domestic sites as can be illustrated by material from Qantir (Raedler 2007; Prell 2011, 92) and Elephantine (Kopp 2005b; see also Budka 2010c). Such a reuse of ceramics is also attested in Nubian cultures, e.g. for cosmetic palettes (Williams 1993, 45 with note 49).

It comes therefore as no surprise that the small finds of our new excavation area within the Pharaonic town of Sai Island, SAV1 East, comprise a large number of reused sherds, similar to SAV1 North. From a total of 322 registered finds from SAV1 East, 103 have been classified as reused sherds. Among these 103 pieces, 17 can be dated to the 18th Dynasty, another 3 as more general to the New Kingdom and 4 pieces are from Nubian sherds of unclear date, but with a possible origin in the New Kingdom.

In sum, only 20% of all the reused sherds are connected with the Thutmoside activity at SAV1 East. The majority originates from the Post-New Kingdom. The objects securely dated to the 18th Dynasty include: 7 ring bases of dishes, re-cut to be used as lids or covers, 5 scrapers, 4 fragmented pieces of unclear function (most probably also used as scrapers) and 1 small disk, possibly a token.

Among the scrapers, a preference for Nile silt plates and dishes is notable; only SAV1E 290 is a reworked piece from a Marl clay vessel – this scraper was re-cut from a large storage vessel, a type known as meat jar. As yet, no fishing weights in the shape of reused sherds – commonly attested at Egyptian sites, e.g. at Elephantine – have been found at SAV1 East.

In sum, although still much smaller in number, the types and variants of reused sherds discovered in 2013 at SAV1 East parallel the findings from five years of excavation in SAV1 North. Further fieldwork will investigate whether this is accidental based on the small quantity, or whether this group of artefacts reflects similar activities in the different sectors of the Pharaonic town of Sai Island.

References:

Budka 2010 = Budka, J., Review of Die Keramik des Grabungsplatzes Q1 – Teil 2; Schaber – Marken – Scherben. Forschungen in der Ramses-Stadt, Die Grabungen des Pelizaeus-Museums Hildesheim in Qantir – Pi-Ramesse 5, ed. by E. B. Pusch & M. Bietak, Hildesheim 2007, Orientalische Literaturzeitung 105/6, 2010, 676–685.

Kopp 2005 = Kopp, P., VI. Small finds from the settlement of the 3rd and 2nd millenium BC, 17, in: D. Raue et al., Report on the 34th Season of Excavation and Restoration on the Island of Elephantine [http://www.dainst.org/sites/default/files/medien/en/daik_ele34_rep_en.pdf?ft=all]

Peña 2007 = Peña, J. T., Roman Pottery in the Archaeological Record, Cambridge 2007.

Prell 2011 = Prell, S., Einblicke in die Werkstätten der Residenz. Die Stein- und Metallwerkzeuge des Grabungsplatzes Q1, Forschungen in der Ramses-Stadt, Die Grabungen des Pelizaeus-Museums Hildesheim in Qantir – Pi-Ramesse 8, Hildesheim 2011.

Raedler 2007 = Raedler, C., Keramikschaber aus den Werkstätten der Ramses-Stadt, 1–266, in: E. B. Pusch (ed.), Die Keramik des Grabungsplatzes Q I – Teil 2. Schaber – Marken – Scherben, Forschungen in der Ramses-Stadt, Die Grabungen des Pelizaeus-Museums Hildesheim in Qantir – Pi-Ramesse 5, Hildesheim 2007.

Williams 1993 = Williams, B. B., Excavations at Serra East. A-Group, C-Group, Pan Grave, New Kingsom, and X-Group Remains from Cemeteries A-G and Rock Shelters, OINE X, Chicago 1993.

The cosmopolitan inhabitants of New Kingdom Sai?

Having read a very interesting article this week, I would like to come back to the subject of Egyptian imitations of Aegean vessels and imported fine wares in contexts of the New Kingdom town of Sai Island.

Caitlin Barrett 2009 investigates “The Perceived Value of Minoan and Minoanizing Pottery in Egypt” – by reviewing the archaeological contexts and by comparing this evidence to the textual and iconographic data, Barrett comes up with some very interesting thoughts on Egyptian attitudes towards Minoan goods.

Minoan vessels were obviously highly valued by the Egyptians of the 18th Dynasty (Barrett 2009: 221), but are not restricted to the elite as they are attested in contexts of various social strata, with diverse socioeconomic backgrounds. I find the following especially thought-provoking: “During the Late Bronze Age, then, Egyptians may have valued Minoan ceramic imports not only because they were specifically Minoan, but also, more generally, because they came from this international sphere. The use of foreign objects and design motifs would have given private individuals a way to participate in this far-ranging koiné, demonstrating their sophistication and cosmopolitanism.” (Barrett 2009: 225)

Within the context of Sai this line of thought opens a lot of questions: Was it appealing for the Egyptians living on Sai to be perceived by the local inhabitants as cosmopolitan Egyptians? Was the range of painted ceramic vessels, so different from the Nubian pottery style, used to demonstrate the sophistication of the officials? Or was it perhaps important for an Egyptian himself, living abroad, to surround himself with things and objects evoking the international sphere from cities like Memphis and Thebes back home?

Pottery as one of the main classes of material culture in ancient settlements was of prime importance for daily activities but ceramic vessels are also carrying information about the identity of its user. This holds especially true for vessels related to food preparation and consumption, but equally for other types within the large corpus of settlement pottery with various functional aspects. I wonder whether the considerable amount of imported (not Egyptian) vessels on Sai in the early-mid 18th Dynasty, with a large number of painted jars, contributed to create a “home away from home” for an Egyptian official in the 18th Dynasty. The complex mixture of ceramics, including imitations of Minoan vessels like the pottery rhyton N/C 1205, might have allowed the temporary inhabitants of Upper Nubia to participate in the international age in vogue at home. Or at least to fake a sophisticated life according to the standards at home.

Apart from this attractive idea of an active role of ceramic vessels in creating “Pharaonic life style” on Sai Island (cf. Barrett 2009: 227), it is also possible that imported vessels were regarded, especially in Upper Nubia and maybe by (Egyptianized) Nubians, as simply pretty “knick-knacks with exotic cachet” (Barrett 2009: 226). However, as objects never have one single meaning, it remains to be tested how the entire ceramic corpus of New Kingdom Sai contributes to the reconstruction of life styles on the island.

Reference:

Barrett, Caitlin E., The Perceived Value of Minoan and Minoanizing Pottery in Egypt, Journal of mediterranean archaeology 22, 2009, 211-234.

The “fire dogs” of Sai – a work in progress

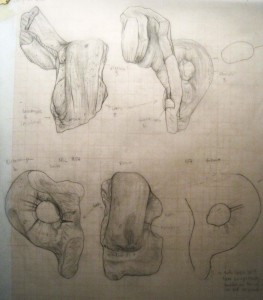

From the end of January till the middle of March I joined the excavation on Sai Island, being responsible for drawing pottery and working on my M.A-thesis at Humboldt University Berlin with a very interesting object group as the subject: the so called “fire dogs”.

These pottery objects are in common scientific opinion described as a helping device for heating pots (see Aston 1989). The fortunate fact that a big number of “fire dogs” has been discovered in the Pharaonic town of Sai, offers a great opportunity understanding and evaluating these items more thoroughly. The basic outward appearance of a “fire dog” vessel is more or less a wheel made, bowl-like body with protruding elements like a handle or a knob at one side and mostly two “legs” or “ears” on top. In addition several pierced holes complete the look of the object.

At the moment my corpus of “fire dogs” consists of 126 pieces – from small fragments of the ear right up to a few half preserved objects that give an impression of the overall shape. The “fire dogs” from Sai show a variety in size, the majority offers an impression of folded ears and in general burned parts can be recognized.

With the aid of the vast number of fragments, some interesting facts concerning the shape, function and manufacturing process can and will be figured out.

At present, at least two different production types are distinguishable:

a) The protruding elements are added to a massive, round body in form of a bowl. It seems as if the “ears” have been made out of a wrapped clay layer and then being attached to the body.

b) The body is constructed like a bowl-like vessel but then cut half in the middle. As a result, the two ears can be folded to the sites into the typical position. Therefore the overall shape of this type is probably made out of one piece and hollow inside.

More food for thoughts are the handles, which are added to a few examples instead of a knob. At one handle, some marks which resemble cuts can be discovered at the inside part of it. Another point is the sometimes very flat rim with small punctured impressions. Pamela J. Rose proposes for her examples from Amarna the idea that maybe the process of drying flattened the rim while the “fire dog” stood on it (Rose 2007, 50). However, not all “fire dogs” from the New Kingdom town of Sai provide this feature.

Especially the traces of use, like burning or abrasion, shall help identifying the function of this pottery type. At the moment some hints support the general assumption that “fire dogs” have been used to hold something over fire by standing on their 3 possible floor spaces (two legs and the knob or handle). In spite of that, there are also other examples that will need a new evaluation and explanation. A kind of multifunctional use within the object group seems likely.

During the 2013 season on Sai, I focused on collecting data, grouping the pieces, making drawings for documentation and taking photos of the objects. The next step here in Berlin is the analysis of the material in form of my M.A.-thesis. Still unanswered questions will hopefully find a solution by conclusive arguments based on the material from Sai and comparisons with other sites.

Besides all the scientific aspects I am very grateful to work with that material on my studies. It is a very nice opportunity for a student to get into contact with the “real” work of an archaeologist, having to make up one’s mind how to organize your “own project”. So all my thanks to Julia Budka and especially to the ancient inhabitants of Sai for this interesting left over from their past.

References:

Aston, D. A 1989: Ancient Egyptian “Fire Dogs” – A New Interpretation, MDAIK 45, 27–32.

Rose, P. J. 2007: The Eighteenth Dynasty pottery corpus from Amarna, EES Excavation Memoir 83, London.

Egyptian imitation of Aegean vessels: A rhyton from Sai

Last week, some of the Aegean imports found on Sai Island in contexts of the 18th Dynasty were mentioned. Today, I would like to present a so far unique piece from SAV1 North.

It is the lower part of a decorated rhyton, covered in a red slip and burnished, made in a very fine Nile B (SAV1N N/C 1205). The conical vessel shape is characteristically Aegean; it is an Egyptian imitation of a Late Minoan IA rhyton, known from other sites in Egypt (especially finds from Tell el-Daba/Ezbet Helmi, see Hein 2013: fig. 6; cf. also Egyptian faience versions of Aegean rhyta, Vermeule 1982). Rhyta are attested in various shapes and types, but as a rule they have a secondary opening apart from the mouth. This also holds true for N/C 1205 which was perforated at its base.

The area around the perforated bottom of N/C 1205 is painted in black with floral elements. Just above these lotus flowers a register with figural painting is still partly visible. It seems to be a scene in the marshes: a striding male figure is carrying two fishes hanging from a pole set on his shoulder. This motif finds a close parallel in one of the silver vessels from the famous Bubastis hoard, characterised by a mixture of Near Eastern and Egyptian styles and motifs (see Bakr/Brandl 2010). Further parallels can be named from the tomb decoration of Egyptian private tombs, especially of the Middle Kingdom and the 18th Dynasty at Thebes.

What may be the function of such an extraordinary vessel in the New Kingdom town of Sai? Similar as the precious metal vessels from Bubastis, also pottery rhyta like N/C 1205 probably had the character of luxury items (cf. Hein 2013). Furthermore, the Egyptian “fish” motif as part of a little marsh scene might be interpreted as a symbol of renewal (cf. Minault-Gout 2004: 120; Stevens 2006: 55-56, 180). Such a general sphere of creation is also evoked by a small pottery figure vase in the form of a fish, a tilapia nilotica, which was discovered in one of the 18th Dynasty tombs at Sai (Minault-Gout 2004: 120; Minault-Gout/Thill 2012: 55-67, tomb 8, no. 87, pl. 160). This remarkable zoomorphic vessel (Khartoum SNM 31319) is, like N/C 1205, a fine red slipped and burnished Nile clay, decorated with black paint. Figure vessels of this type are rare, but another example was found in Upper Nubia at Soleb (see Bourriau 1982: 103-104, no. 86.)

All in all, the Egyptian rhyton from Sai Island illustrates not only the international age of 18th Dynasty Egypt and contacts to the Aegean, but it also refers to important aspects of daily life like creation and fertility.

References

Bakr/Brandl 2010 = M. I. Bakr/H. Brandl, Precious metal hoards from Bubastis, in M.I. Bakr/H. Brandl with F. Kalloniatis (eds.), Egyptian Antiquities from Kufur Nigm and Bubastis, Berlin, 2010, 43-53.

Bourriau 1982 = J. Bourriau, No. 86: Fish vase, in E. Brovarski/S.K. Doll/R.E. Freed (eds.), Egypt’s Golden Age: The Art of Living in the New Kingdom, exhibition catalogue, Museum of Fine Arts Boston, 103-104.

Hein 2013 = I. Hein, Cypriot and Aegean features in New Kingdom Egypt: cultural elements interpreted from archaeological finds, in P. Kousoulis/N. Lazaridis (eds.), Tenth International Congress of Egyptologists, University of the Aegean, Department of Mediterranean Studies, Rhodes 22-29 May 2008 (Orientalia Lovaniensia Analecta), Leuven, 2013 [in press].

Minault-Gout 2004 = A. Minault-Gout, Cat. 95: Figure vase in the form [of] a fish, in D.A. Welsby/J.R. Anderson (eds.), Sudan. Ancient Treasures. An Exhibition of recent discoveries from the Sudan National Museum, London, 2004, 120.

Minault-Gout/Thill 2012 = A. Minault-Gout/F.Thill, Saï II. Le cimetière des tombes hypogées du Nouvel Empire (SAC5) (FIFAO 69), Cairo, 2012.

Stevens 2006 = A. Stevens, Private Religion at Amarna (British Archaeological Reports, International Series 1587), Oxford, 2006.

Vermeule 1982 = E.T. Vermeule, Egyptian Imitations of Aegean Vases, in E. Brovarski/S.K. Doll/R.E. Freed (eds.), Egypt’s Golden Age: The Art of Living in the New Kingdom, exhibition catalogue, Museum of Fine Arts Boston, 152-153.

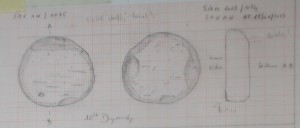

The tiny highlight of this week: a frog amulet

A very small faience object delighted us this week: a nicely done, really tiny (only 8 mm in lenght!) amulet in the form of a squatting frog with open mouth came up while cleaning around feature 28, the Post-New Kingdom stone foundation in Square 2b. It is in fact an uninscribed frog amulet or scaraboid as the flat, oval base was left uncarved.

The amulet was obviously once used on a string – whether on a necklace or a bracelet remains open – it has a regular perforation at its lateral side, piercing the amulet in the centre, not longitudinally. Unfortunately, the archaeological context – found in dense mud debris with mixed ceramic material, filling material of the depression south of feature 28 – does not provide any glue for dating.

In Ancient Egypt, frogs were primarily associated with fecundity, (female) fertility and birth – they are common amulets used during a long time span, both for the living and in funerary contexts. Beads in the form of frogs are also well known from New Kingdom domestic contexts – for example in Egypt in Amarna (see Anna Stevens 2006. Private religion at Amarna, pp. 56-57) – however, the frogs there differ in shape and have a characteristic upraised head. Very small frog pendants or amulets are reported from Eighteenth Dynasty votive contexts in Egypt – these I will have to check back home with a proper library! It would of course be tempting to connect SAV1E 294 with the temple area in the Pharaonic town of Sai! But as amulets in form of frogs survived well beyond the New Kingdom, until the Ptolemaic time and were also common in later phases of Nubian cultures (e.g. in Napatan tombs), I definitely want to deepen the search for parallels before our small frog from SAV1E can be tentatively dated by analogies! Regardless of its date, it is a very nice artefact and one of this season’s favorites!

In Ancient Egypt, frogs were primarily associated with fecundity, (female) fertility and birth – they are common amulets used during a long time span, both for the living and in funerary contexts. Beads in the form of frogs are also well known from New Kingdom domestic contexts – for example in Egypt in Amarna (see Anna Stevens 2006. Private religion at Amarna, pp. 56-57) – however, the frogs there differ in shape and have a characteristic upraised head. Very small frog pendants or amulets are reported from Eighteenth Dynasty votive contexts in Egypt – these I will have to check back home with a proper library! It would of course be tempting to connect SAV1E 294 with the temple area in the Pharaonic town of Sai! But as amulets in form of frogs survived well beyond the New Kingdom, until the Ptolemaic time and were also common in later phases of Nubian cultures (e.g. in Napatan tombs), I definitely want to deepen the search for parallels before our small frog from SAV1E can be tentatively dated by analogies! Regardless of its date, it is a very nice artefact and one of this season’s favorites!

Organising finds & objects

At the end of week 7, our File Maker database comprises all objects excavated in 2013. 278 finds have been registered so far – these are  mostly stone tools, grinding stone fragments, re-used sherds but also some fayence beads and clay objects. The database gives some basic information, a short description and all measurements of the individual finds.

mostly stone tools, grinding stone fragments, re-used sherds but also some fayence beads and clay objects. The database gives some basic information, a short description and all measurements of the individual finds.

Each piece was recorded by digital photographs; selected finds were also drawn in 1:1. Drawing of small finds will continue in the next 2 weeks on Sai.

But as Nathalie who was in charge of the object database is unfortunately already leaving this weekend, we have started packing some of the registered objects in boxes for future storage. As much as we will miss our chief registrar as a person, there is nothing missing or left to finish, all was thoroughly organised – many thanks for a perfect job as usual!

Fire dogs … and other adorable canines!

Nicole Mosiniak, a MA student from Humboldt University Berlin and skilled draftsperson with a lot of experience in documenting ceramics from Egypt, just started her research on the so called “fire dogs” from the Pharaonic town of Sai Island.

The nick name of these ceramic vessels (of which we found large numbers) derives from hopefully clear associations: a snout-like nose, two eye-like perforations and two long conical ear-like extensions (some archaeologists have had also connotat ions with pigs, which are not as convincing because of the long ears)! Although the functional use of these vessels is not precisely known, they are usually connected in Egyptological literature with processes involving fire and burning, most likely cooking.

ions with pigs, which are not as convincing because of the long ears)! Although the functional use of these vessels is not precisely known, they are usually connected in Egyptological literature with processes involving fire and burning, most likely cooking.

Nicole aims at reassessing these ideas and will report about her recent findings herself in the near future!

As our team is full of dog-lovers apart from Nicole, we are very happy that we could extend our affection for canine creatures: from the New Kingdom “fire dogs” to another simply adorable representative of canines: Thanks to the Sudanese school holidays, the digging house became the temporary residence of our cook’s family puppy-dog – with the multi-lingual education and attention she is currently receiving, a dog with a most promising future!