Fishing played obviously a role in daily life at Sai Island, also during the 18th Dynasty. A number of clay net weights, Egyptian in character, attest to local fishing by the occupants – at our new excavation area SAV1E just two net weights have been found in 2013; 20 more pieces have been documented at SAV1N between 2008 and 2012.

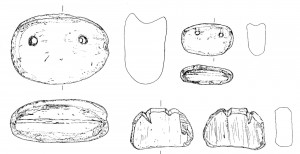

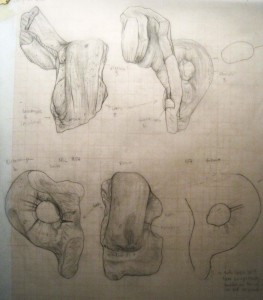

This type of weight for fishing nets is well known from Middle Kingdom models found in Egyptian tombs; corresponding artefacts have been documented at major fortresses in Lower Nubia like Buhen and Askut, sites which flourished in the Middle Kingdom (see Smith 2003, 1010). Large variants of such clay net weights with two perforations, resembling the shape of axe-heads, have been dated to the Middle Kingdom. At Sai Island, the size of the objects may vary from very small to middle and large within New Kingdom contexts and such a dating might therefore require a reassessment or at least a site specific chronology. Besides the “axe-head”-type, net weights appear also as re-cut sherds at SAV1N.

Elephantine provides contemporaneous parallels for both types of net weights from the Pharaonic town on Sai Island. von Pilgrim 1996 has classified the “axe-head” version as type A and re-cut sherds as type C. Interestingly, the distribution of the specific types of weights differs notably between Elephantine and Sai Island. For Level 10 at Elephantine, which is contemporaneous to Level 4 and partly Level 3 at SAV1N, 75.9 % of the net weights are type C (re-cut sherds) and 24.1 % type A (clay object with perforations) (von Pilgrim 1996, 279, fig. 123). The evidence from SAV1N is almost reversed: 17 weights are of von Pilgrim’s type A (= 85 %) and only three (15 %) of type C. Both examples from SAV1E are belonging to type A, thus supporting the dominance of this type of gear on the island.

This notable difference regarding the net weights from 18th Dynasty contexts at Sai Island and Elephantine remains to be investigated in the future. Could it be just an accidental finding, due to the still very small number of weights from Sai? Or might it reflect differences between the fishing gear in Egypt and Upper Nubia? Maybe the Middle Kingdom “axe-head” type was more popular and longer in use in Nubia than in Egypt. von Pilgrim has also proposed that type C at Elephantine, recycled from pottery sherds, is the cheap and ad hoc product for individual needs (von Pilgrim 1996a, 275–278). One could therefore speculate whether the distribution of net weights at Sai was primarily organized at a higher level. Type A might have been imported to Sai from Egypt and fulfilled the local demand for the most part. The need for an ad hoc production of type C would have been consequently less common than at Elephantine. Such a “centralized system of food production” as a reflection of the use of net weights of type A was already suggested by Smith for the Middle Kingdom phase at Askut (Smith 2003, 101). However, as we still do not know the size of the community living on Sai during the New Kingdom, any thoughts about demands and strategies for food production must remain very tentative for now.

References:

von Pilgrim 1996 = C. von Pilgrim, Elephantine XVIII. Untersuchungen in der Stadt des Mittleren Reiches und des Zweiten Zwischenzeit, AV 91, Mainz am Rhein 1996.

Smith 2003 = St. T. Smith, Wretched Kush. Ethnic identities and boundaries in Egypt’s Nubian Empire, London and New York 2003.