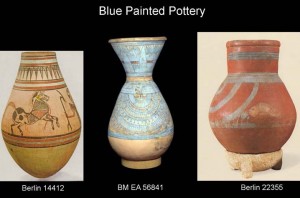

At present, analysing semiotic aspects of ancient pottery is quite on vogue in archaeology (cf. Preucel 2010: 230–238 and passim). I do see much potential in this approach and I have recently presented a small case study on Blue painted pottery (Budka 2013). Of course there are clear limits of possibilities to reconstruct ancient ideas and symbolism – nevertheless the famous Blue painted ware with ornamental Hathor vessels (for which see most recently the great post by Anna Garnett, Manchester Museum), Bes jars and mostly floral decoration nicely illustrates that such New Kingdom vessels had a symbolic value, probably with several semantic layers.

The colour blue may have referred to faience and glass instead of pottery in the first place. Colin Hope assumed a time-specific taste for the Blue painted pottery: “The impetus for its manufacture undoubtedly lay in the taste for elaboration during an age of luxury” (Hope 1982, 88). A preference for blue as a matter of taste and an expression of a specific Zeitgeist seems indeed likely (cf. Budka 2013). Here it is important that as archaeologist we take into account a wide range of emotions possibly associated with objects in various contexts and in different social strata – of course these associations cannot be kept apart from culture and society in general (cf. Tarlow 2000, 713). The aesthetic qualities of Blue painted vessels are usually highly valued in the eyes of modern Egyptologists – but can we trace aspects of its approval in the mind of the Ancient Egyptians? It is striking that common vessel types like simple beakers and dishes appear together with special, large ornamental vessels with complex applications within the corpus of Blue painted ware (cf. Budka 2008). Thus, sometimes the only difference to well-known vessel types of the New Kingdom is simply the decoration. Here the colour blue and the common floral motifs (painted or moulded) like the blue lotus seem to refer to wide-ranging creative aspects and especially to rebirth (cf. Budka 2013).

For a short time, Blue painted pottery formed an integral component of the material culture of the New Kingdom, both of the domestic equipment and of the votive offerings for temples and sanctuaries. Similar to painted wares in various cultural contexts around the world, it may have “served as the good china of the day” (Wonderley 1986, 506). Because of the particular character of the ware daily activities for which Blue painted pottery was used, received a special connotation. I don’t think that the simple presence of blue painted or other “exotic” vessels in domestic settings do necessarily suggest a “palace character”, a comfortable lifestyle or high status of its inhabitants: they point rather to the presence of religious, cultic or festive activities respectively the evocation of such a sphere.

Blue painted pottery is present at all sites investigated within the framework of AcrossBorders – at Sai, Elephantine and also at Abydos. But the number of sherds found at Sai is still very limited – maybe this is one of the differences to the Egyptian sites. However, there is the possibility to investigate the multiple semantic layers of ceramic vessels with another case study for our project: a group of decorated vessels in red-and-black painted (Bichrome) style. These vessels are attested in Egypt both in Nile clay and in Marl clay variants, whereas in Upper Nubia preferably Nile silt versions are known (Ruffieux 2009; Budka 2011).

Based on a number of closely similar fragments from Elephantine and Sai, we will try to find possible answers to the question whether the specific decorative bichrome painted style and the most common motifs like antelopes, horses and flowers have a similar symbolic value for its users, both in Egypt and Upper Nubia. Our last week at Elephantine will therefore focus on the documentation of these very specific red-and-black painted vessels.

My New Kingdom pottery database of Elephantine counts a total of 52 Nile clay vessels and 52 Marl clay bichrome painted sherds which will enable us to address some of the questions outlined here.

References

Budka 2008 = VIII. Weihgefäße und Festkeramik des Neuen Reiches von Elephantine, in G. Dreyer et al., Stadt und Tempel von Elephantine, 33./34./35. Grabungsbericht, in Mitteilungen des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts, Abteilung Kairo 64, 106–132.

Budka 2011 = J. Budka, The early New Kingdom at Sai Island: Preliminary results based on the pottery analysis (4th Season 2010), in Sudan & Nubia 15, 23–33.

Budka 2013 = Festival Pottery of New Kingdom Egypt: Three Case Studies, in Functional Aspects of Egyptian Ceramics within their Archaeological Context. Proceedings of a Conference held at the McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research, Cambridge, July 24th – July 25th, 2009, ed. by Bettina Bader & Mary F. Ownby, Orientalia Lovaniensia Analecta 217, Leuven, 185–213.

Hope 1982 = C.A. Hope, Blue-Painted Pottery, in E. Brovarski, S.K. Doll and R.E. Freed (eds.), Egypt’s Golden Age: The Art of Living in the New Kingdom, Exhibition Catalogue, Boston, 88-90.

Preucel 2010 = R. W. Preucel, Archaeological Semiotics, Malden and Oxford.

Ruffieux 2009 = P. Ruffieux, Poteries découvertes dans un temple égyptien de la XVIIIe dynastie à Doukki Gel (Kerma), in Genava 57, 121-134.

Tarlow 2000 = S. Tarlow, Emotion in Archaeology, in Current Anthropology 41, no. 5, 713-745.

Wonderley 1986 = A. Wonderley, Material Symbolics in Pre-Columbian Households: The Painted Pottery of Naco, Honduras, in Journal of Anthropological Research 42, no. 4, 497-534.